Willy Blum

The "forgotten" child on the list

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Willy Blum was born in Rübeland (in the Harz Mountains) on 26 June 1928, the eighth of ten children. His father Alois and his mother Toni owned a travelling puppet theater. In 1943, the police deported the “gypsy” family to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On 3 August 1944, after the dissolution of the Auschwitz “Gypsy family camp,” Willy and his ten-year-old brother Rudolf were sent to Buchenwald. At the end of September, Rudolf was to be deported back to Auschwitz and thus to certain death. Willy decided to go with his brother and volunteers for the transport, for which Stefan Jerzy Zweig was originally also scheduled. The two brothers, Willy and Rudolf, were presumably murdered by the SS shortly after their arrival in Auschwitz.

The failure to commemorate Willy Blum before 2018 contrasts with the world-famous heroic rescue story of the “Buchenwald child” Stefan Jerzy Zweig.

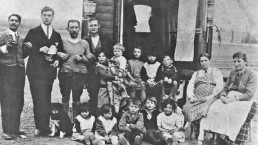

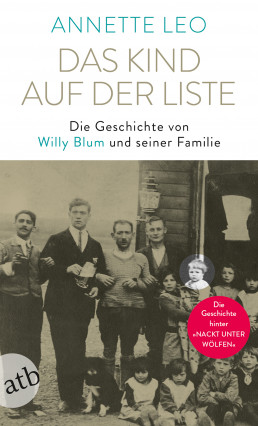

The Blum and Elsner puppeteer families in front of their caravan. Two-year-old Willy (center) is held by sister Anna, 1930.

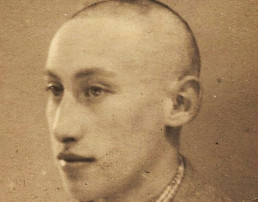

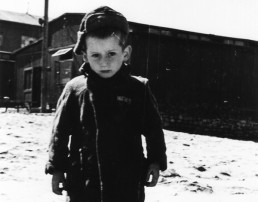

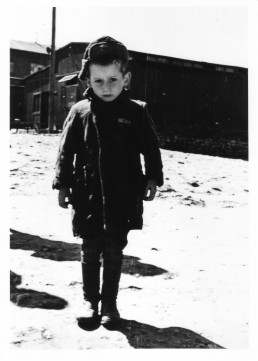

This is the only existent photograph of Willy Blum. The Blums had been showmen for generations, moving from place to place to perform their art. All family members except Willy and Rudolf survived.

(private property)

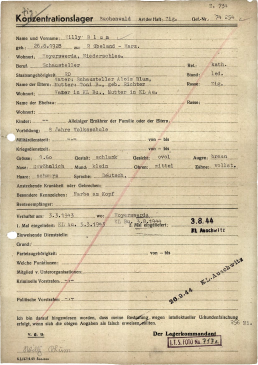

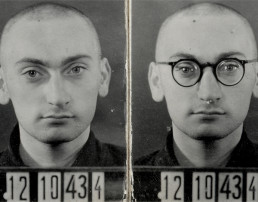

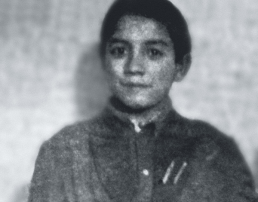

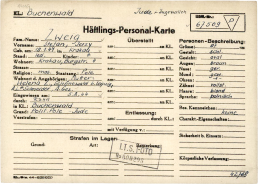

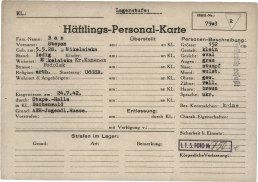

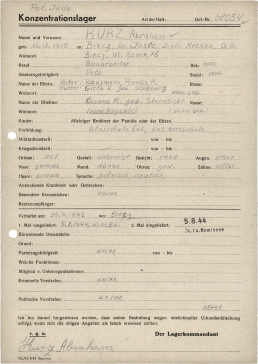

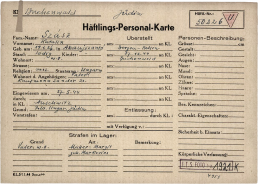

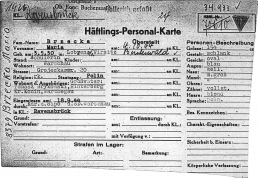

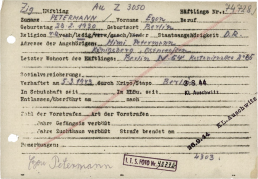

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for 16-year-old Willy Blum, 3 August 1944.

Willy Blum arrived at Buchenwald on a transport from Auschwitz on 3 August 1944, together with his ten-year-old brother Rudolf. The document lists the reason of his arrest as “Gypsy.”

(Arolsen Archives)

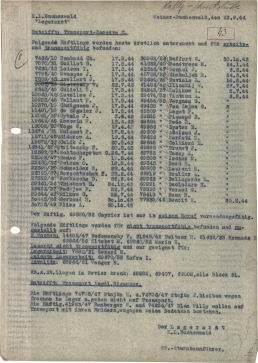

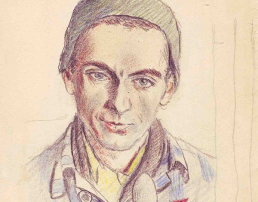

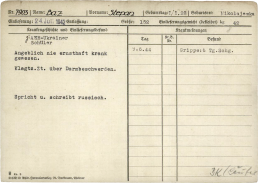

"... to which there are no objections." The Buchenwald camp physician confirms Willy Blum's fitness for transport, 23 September 1944.

The Buchenwald SS physician Dr. Bender certified the two Sinto boys Willy Blum and Walter Bamberger as fit for transport after an examination; both “want to be transported with their brothers.”

(Arolsen Archives)

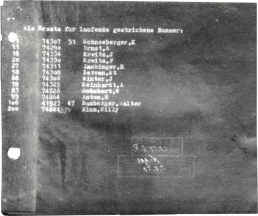

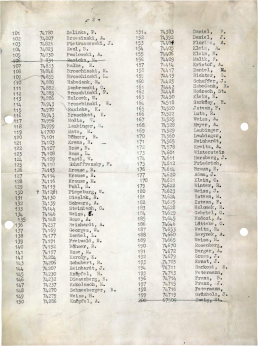

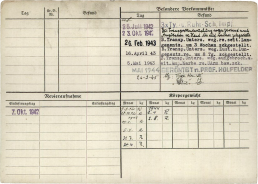

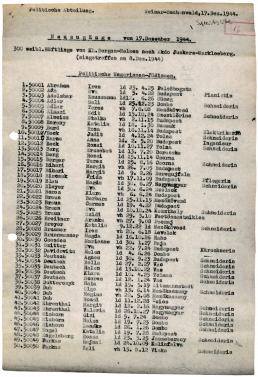

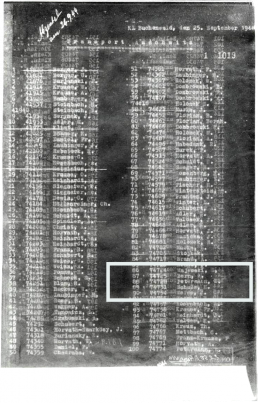

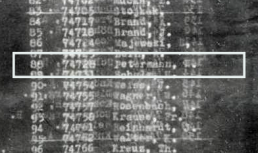

Addendum to the list for transport to Auschwitz, 25 September 1944.

Willy Blum, number 200, was entered as a replacement for Stefan Jerzy Zweig.

(Arolsen Archives)

Belated memorialization. Cover of the book Das Kind auf der Liste by Annette Leo, 2018.

It was not until 2018 that Annette Leo researched and reconstructed the story of Willy Blum and his family. She published her findings in 2018 in the book Das Kind auf der Liste (The Child on the List).

(Aufbau Verlag)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Memorial stone for Willy Blum as part of the Buchenwald Railway Memorial Stones project:

gedenksteine-buchenwaldbahn.de.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Stefan Jerzy Zweig

The famous Buchenwald child

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Stefan Jerzy Zweig was born on 18 January 1941 in Krakow to the lawyer Zacharias Zweig and his wife Helena. Together with his parents and his sister Sylwia, who was eight years his senior, he survived the Krakow Ghetto and several camps in Poland.

In the summer of 1944, the family was separated on a transport. The mother and sister were sent to the Leipzig-Thekla subcamp and were later murdered in Auschwitz. Three-year-old Stefan was deported to Buchenwald with his father. There, with the help of political prisoners, Zacharias Zweig managed to ensure the survival of his son.

After the war, father and son lived in Poland and France, and later emigrated to Israel. As the “Buchenwald Child” in Bruno Apitz’ novel Naked Among Wolves (1958), Stefan Zweig became world famous. He himself only learned of the fictionalized rescue story after the 1963 film based on the novel. In 1964, he visited the GDR and there met his future wife, with whom he has lived in Vienna since 1972.

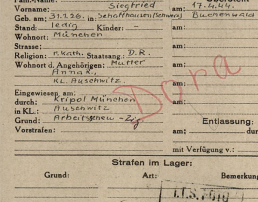

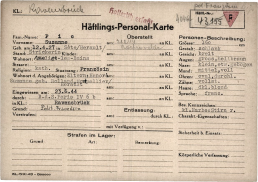

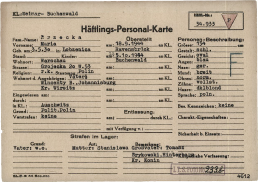

Prisoner registration file for three-year-old Stefan Jerzy Zweig, 5 August 1944.

Stefan Jerzy Zweig was registered at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 5 August 1944, together with his father Zacharias Zweig. The reason given for his imprisonment was his classification as a Polish Jew and political prisoner. In the upper part of the card is noted Jude-Jugendlich (Jew, youth).

(Arolsen Archives)

Removed from the list. Second page of the transport list from Buchenwald to Auschwitz, 25 September 1944.

At the end of September 1944, the SS ordered a transport of 200 children and adolescents to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Stefan Jerzy Zweig was initially on the transport list (No. 200). In order to save him, his father took him to the camp’s typhoid fever ward and had him injected with a fever-inducing drug. Stefan was declared unfit for transport and escaped certain death in Auschwitz. In his place, the SS deported the 16-year-old Sinto Willy Blum to Auschwitz.

(Arolsen Archives)

"I could not believe my eyes! My child was dressed very nicely. He was wearing a suit specially tailored for him and sewn in the workshops for prisoners. He had on a well-tailored blouse of new fabric, dark blue with white stripes. He wore short pants and new shoes made especially for him. When I arrived, he was playing with toys."

Zacharias Zweig recalls his son's camp clothes at Buchenwald, 1987.

(“Mein Vater, was machst du hier..? Zwischen Buchenwald and Auschwitz.” An account by Zacharias Zweig, edited by Berthold Scheller in cooperation with Stefan Jerzy Zweig, Frankfurt a.M. 1987).

"The struggle for this child is proof of the greatness and beauty and not least of the victory of man over barbarism."

Bruno Apitz in the trailer for the DEFA film Naked Among Wolves, directed by Frank Beyer, 1963.

The fictionalized rescue of Stefan Jerzy Zweig by communist prisoners in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp served to heroize anti-fascist camp resistance in the GDR.

(DEFA Foundation)

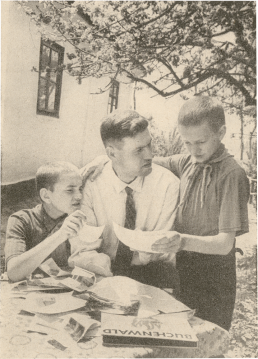

Stefan Jerzy Zweig (left, with cap) meets author and former prisoner Bruno Apitz (right) during a visit to the Buchenwald National Memorial, 1964.

Stefan Jerzy Zweig first learned of his role in the novel Naked Among Wolves and the film adaptation in 1964. Journalists tracked him down in France and he was invited to the Buchenwald memorial. The meeting with Apitz was staged as a propaganda event.

(Photo: Norbert Schwarz, Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Stepan Baz Labor re-education prisoner in Buchenwald

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Stepan Grigorjevitsch Baz was born in Nikolajewka (Ukraine) on 5 May 1927. In 1942, he was deported to Germany as a forced laborer, and from July 1942 onwards the 15-year-old had to work near Halle. In the middle of the month, his workplace reported him missing. A short time later, the Halle state police delivered him to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp via the Watenstedt camp. He was registered as a labor re-education prisoner.

He was assigned to forced labor at the Gustloff-Werk II armaments factory. When he was accused of sabotage in the fall of 1942, the SS placed him in a holding cell and later amputated his right hand. Fritz Unger and other communist prisoners found the injured boy in the infirmary and took care of him. Their help made it possible for Stepan Baz to survive Buchenwald.

Two weeks after liberation, Baz returned to his family in Ukraine. There, he married and has two children. Stepan Baz died on 7 December 2016.

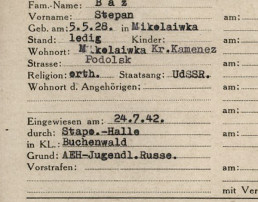

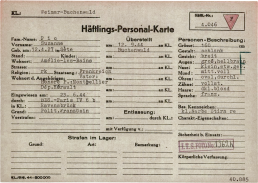

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Stepan Baz, 24 July 1942.

According to his own statements, Stepan Baz was born on 5 May 1927; on his prisoner’s personal card and other documents from Buchenwald, he was listed as one year younger. At Buchenwald Concentration Camp, he was registered as an AEH Jugendliche (labor re-education youth) Baz was one of the first juvenile labor re-education prisoners in Block 8, which housed mainly adolescents and children from 1942 onwards.

(Arolsen Archives)

"But I didn't want to work for the fascists, and then I was sent to the concentration camp. [...] In the concentration camp I had to work again, you know: all the procedures that were supposed to happen before, and then to work again, in the Gustloff factory. I worked like this, there were two German comrades there - prisoners, maybe - and I was supposed to help them, but I helped 'the other way around'. I don't know what to call it properly, there were mechanisms that had to cut out various details, and I broke those little by little. Then the SS supervisor saw it and took me upstairs, to the gate. And then the interrogations started [...]. They asked me several times, beat me very badly, locked me in the cell."

"...and I broke them little by little". Interview with Stepan Baz about his sabotage at the Gustloff factory, 2009.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Condition after amputation." Buchenwald Concentration Camp infirmary file for Stepan Baz, 1942-45 (front and back).

After his detention, an SS doctor amputated Stepan Baz’s right hand. The consequences are noted in the infirmary: his wounds did not heal, and as late as May 1943, the scar was festering. During transport examinations, which were supposed to release him for forced labor assignments, he was deferred several times and was thus able to remain in Buchenwald.

(Arolsen Archives)

Visiting the GDR. Stepan Baz (l.) with Fritz Unger, 1960s.

Thanks to the help of Fritz Unger and other communist prisoner functionaries, Stepan Baz survived after his hand was amputated. In 1962, Stepan Baz began corresponding with Fritz Unger. They visited each other in the GDR and the Soviet Union. The GDR press reported in great detail about the rescue of the young Ukrainian by German communists.

(private property)

Stepan Baz tells his sons Vitya and Tolya about the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1962.

Baz joined the Communist Party after his return to Ukraine and later became the chairman of a collective farm. He and his wife had two sons. The story of the teenager’s rescue in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp by Communist prisoners was reported several times in the GDR press. Until shortly before his death in 2016, he spoke often as a contemporary witness.

(Und weil der mensch ein Mensch ist…, published by the Society for German-Soviet Friendship, Karl-Marx-Stadt District Board, 1962).

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Estare Weiser (née Kurz)

Born in the concentration camp

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

On 13 April 1945, the HASAG Leipzig subcamp, a part of the Buchenwald camp system, was evacuated as the US Army approached. The approximately 5000 female prisoners were driven on death marches. Only a few women who were too ill or weak for the march remained behind. One of them was the Polish Jew Anna Kurz. She was heavily pregnant – and gave birth to her daughter Estare on the day of the evacuation.

Miraculously, the child survived. On 19 April, the Americans entered Leipzig, liberated the mother and daughter, and took them to a hospital. In June 1945, they were both able to leave for Switzerland with the help of the Red Cross. A year later, Abraham Kurz, Anna’s husband and Estare’s father, joined them there. He survived the Buchenwald subcamp Schlieben and a death march to Theresienstadt.

In 1951, the Kurz family emigrated to the USA. Estare became a history teacher and married the psychiatrist David Weiser in 1967. The couple now lives in New York and has two sons and four grandchildren.

"The Holocaust completely changed their lives. They had lost their families, their homes, their land, their benefits of inherited wealth, their connections, the roots in their culture, and the support of their families. My parents were the only couple from their town, both of whom had survived the Shoah."

Estare Weiser's account of her parents' story, 28 May 2020.

(storyworth.com)

Buchenwald Concentration Camp registration file for Estare's father Abraham Kurz, 5 August 1944.

Abraham and Anna Kurz had been forced laborers in an armaments factory of the Leipzig-based HASAG corporation in occupied Poland. When the Red Army approached in the summer of 1944, the concern relocated the factory to subcamps of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in central Germany. On the form, Abraham’s wife’s name is given as Channa K., and no dependents are listed. Their son Moishele was already dead.

(Arolsen Archives)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Anne Friebel, Geboren im KZ – die Geschichte von Estare Weiser, in: Newsletter of the Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial, Issue 9, December 2020, pp. 14 – 16.

zwangsarbeit-in-leipzig.de.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Suzanne Orts (née Pic)

As a teenager in the Résistance

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Suzanne Pic was born in Sète (France) on 12 April 1927. The Wehrmacht (German armed forces) invaded France in May 1940. Various underground groups resisting the German occupiers and the new regime were organized, and in 1943, they joined together to form La Résistance.

The 16-year-old Suzanne also became active in the Résistance. She was arrested in 1944 during a resistance operation and deported to Germany. Via the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, she arrived at the Buchenwald subcamp HASAG-Leipzig in July 1944. There, she was assigned to forced labor in the armaments industry.

In April 1945, the SS dissolved the camp and drove the women and girls on a death march to the east. She and several other prisoners were able to escape from the death march, and a short time later they were liberated by Soviet soldiers. Suzanne returned to Paris, married Elie Orts and was active in various survivors’ associations until her death in 2018. In 2006, she received the French National Order of Merit.

Ravensbrück Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Suzanne Pic, 23 June 1944.

From Perpignan, Suzanne and her mother were deported to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. She was given the number 43155 and, as a political prisoner, the red prisoner triangle with an “F” for French.

(Arolsen Archives)

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Suzanne Pic, 12 September 1944.

In July, the SS transported Suzanne and her mother to Leipzig-Schönefeld, where they had established the HASAG Leipzig subcamp in June 1944. It was initially a subcamp of the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, but was then transferred to Buchenwald. With 5,000 inmates, it was Buchenwald’s largest women’s subcamp.

(Arolsen Archives)

"12 hours of work, one week during the day, one week at night, on Sundays we rest. In addition, there is always roll call in the morning and evening. Wake-up at 4 o'clock. We make 7-kilo anti-aircraft shells. [...] All day long you have to move these 7 kilos, take them down from a table, hold them to a rotating brush, use a greasy rag to coat them and then put them in the cart. All of that, 200, 300, 400 times a day. [...]."

Account by Suzanne Orts (née Pic) on forced labor as a 17-year-old in the HASAG-Leipzig subcamp, 1993.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

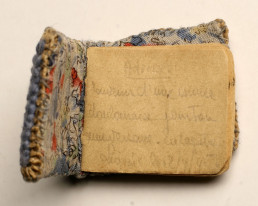

Handcrafted jewelry, 1944/45.

Suzanne Pic secretly made a belt, a brooch, and a cross from scraps of material. In 1944, the prisoners in Leipzig held a small Christmas party where they gave each other small gifts. Suzanne received an address book made of straw, wool, scraps of paper, and cloth, with her initials “SP” embroidered on it.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"In spite of the system of oppression with which they tried to turn us into frightened and fearful sheep, in spite of the harassment and punishment with which they tried to rob us of our humanity, we tried to remain dignified and proud women."

Self-Assertion in the Concentration Camp. Account by Suzanne Orts (née Pic), 1993.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Suzanne Orts (right) at a memorial event together with other survivors of the concentration camp in Leipzig, 13 April 1996.

Suzanne spoke several times with school classes about her experiences, and in the 1990s, she wrote down her story of persecution. She took part in memorial events in Leipzig, where she met other survivors, such as Danuta Brzosko-Mendryk and Zofia Kolecka-Fugiel, as shown in the photo. Together, they worked to reconstruct and make public the history of the former subcamp. Suzanne Orts passed away in February 2018.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial: Concentration Camp Subcamp “HASAG Leipzig” – Largest Women’s Subcamp of Buchenwald Concentration Camp, zwangsarbeit-in-leipzig.de.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Zahava Szász Stessel (née Katalin Szász)

A Hungarian Jew in the Markleeberg subcamp

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Katalin Szász was born in Abaujszántó (Hungary) on 19 January 1930 to Margit and Sándor Szász. After the German occupation, the family was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1944.

Upon arrival in Auschwitz, the 14-year-old Katalin was deemed “fit for work.” She and her sister were deported via the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp to a subcamp of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in Leipzig-Markleeberg. There, the sisters were forced laborers for the SS in armaments production until the end of March 1945.

In April 1945, Katalin and Erszebet were liberated by Soviet troops while on a death march. In the hope of reuniting with their family, they returned to Hungary, but their parents were dead. In 1947, the sisters emigrated to Palestine, where Katalin married and took the name Zahava Szász Stessel. In 1957, she and her husband emigrated to the USA, where she still lives today.

Katalin Szász (right) with her sister, before 1939.

Katalin spent her childhood in Hungary with her younger sister Erszebet (she later changed her name to Hava), her parents, and grandparents. The family owned a store for clothes, shoes, coffee and books. The anti-Jewish laws passed in Hungary in 1939 and 1942 hit the family business hard. Katalin had to quit school early because her parents could no longer afford her tuition.

(Zahava Stessel)

Transport list from Bergen-Belsen to Markleeberg, 17 December 1944 (pages 1 and 4 of 6).

Katalin and her sister (on the list the numbers 225 and 226) pretended to be older when they arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, so that they could be categorized as “fit for work.” They were initially sent to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. In December 1944, both were transferred, along with 300 other women and girls, to the Leipzig-Markleeberg subcamp for forced labor.

(Arolsen Archives)

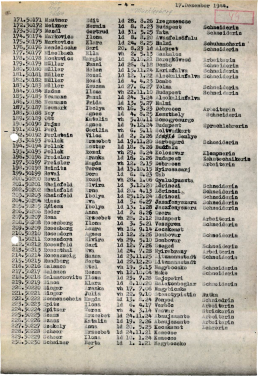

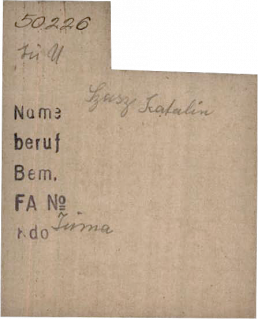

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Katalin Szász, 17 December 1944.

In the Markleeberg subcamp, she was registered as a “polit. ungar. Jüdin” (political prisoner, Hungarian Jewess) and is given the number 50226. Her date of birth is entered as 1926. In fact, she was four years younger.

(Arolsen Archives)

„After some terrible work assignments in a stone quarry, Hava and I were given indoor jobs. Hava was given a job randomly on an automatic machine and I was given the task of sweeping the floors inside the factory around the machines with a heavy broom.”

Zahava Stessel's account of forced labor in Markleeberg, 2021.

The women were put to work in the Junkers-Werke engine plant, where they had to produce airplane parts. Katalin was too small to work on the machine and was given the task of sweeping up the metal filings that fell to the ground. This lighter work saved her life.

(private property)

16-year-old Katalin Szász in the Indersdorf DP camp near Munich, 1946.

After the sisters were liberated by Soviet soldiers while on a death march, they returned to Hungary. They hoped to find at least their father. When they learned that none of their family had survived, they decided to emigrate to Palestine. From a DP camp in the Indersdorf monastery, they traveled via France to Palestine, where they arrived in February 1947.

(Zahava Stessel)

Zahava Stessel with her sister Hava Ginsburg in Leipzig-Markleeberg, 1998.

In the 1990s, Zahava Stessel, together with other survivors, campaigned for the redesign of the memorial plaque, dedicated in 1998, at the former concentration camp subcamp in Markleeberg. Zahava spoke several times for school classes about her camp experiences. In 2008, the city of Markleeberg awarded her honorary citizenship.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Maria Janina Kosk (née Brzęcka)

Drawing and survival in the Meuselwitz subcamp

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Maria Brzęcka was born on 3 May 1930 in Łobżenica (Poland). From 1940 to 1944, she lived with her mother and her sisters Halina and Krystyna in Warsaw, where she attended elementary school.

In 1944, after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising, the mother and the three daughters were deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. From there, they were sent to Ravensbrück and then to the Buchenwald subcamp Meuselwitz. There, they were assigned to forced labor in a munitions factory. At the end of November 1944, the four were separated when their mother and sister Krystyna were sent back to Ravensbrück.

In Meuselwitz, Maria secretly kept a diary and made numerous drawings. On 5 May 1945, Maria and Halina were liberated by Soviet troops while on a death march. They returned to Poland and were reunited with their mother and sister Krystyna. Maria studied architecture and later worked in Poland, France and Algeria. She died in 2013 in Warsaw.

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file, October 1944.

The Meuselwitz Concentration Camp was a subcamp of Buchenwald; the prisoners were registered in the main camp. In the prisoner registration file, the 14-year-old was assigned a red prisoner triangle and categorized as a political prisoner. The file also indicates that she had previously been in the Auschwitz and Ravensbrück Concentration Camps.

(Arolsen Archives)

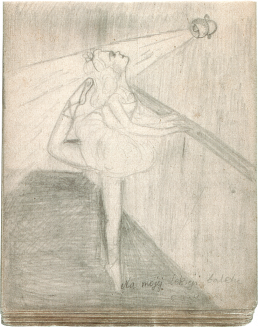

"My ballet class": drawing from the Meuselwitz Concentration Camp, 8 February 1945.

Maria Brzęcka drew in order to escape the reality of the camp. Here, she depicted a memory of her ballet lessons in Warsaw.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Maria Brzęcka’s poetry album from her time in the Meuselwitz Concentration Camp.

On the cover of the album are sewn the red triangle with the letter “P” for Polish and the number she had to wear on her prison uniform.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"One day Halina gave me a pleasant surprise. Since I had finally received new wooden shoes from the warehouse, my sister asked Pani Jadwiga [a fellow prisoner] for some scraps of cloth. From them and from paper she had taken from the factory, Halina made me a poetry album like the one I had owned in Warsaw. My friends would sign the book, usually with a poem. The cover of my poetry album was made of cardboard, covered with dark blue cloth, on which the triangle with the red letter P was sewn. Underneath, on a piece of white cloth, was my number 34933. The kind women imprisoned with me signed my album."

Diary entry by Maria Brzęcka about the creation of the poetry album in the Meuselwitz Concentration Camp, January 1945.

(Als Mädchen im KZ Meuselwitz. Erinnerungen von Maria Brzęcka-Kosk, Dresden 2016).

After liberation. Maria Brzęcka in her apartment in Warsaw, 1951.

Maria Brzęcka returned to Warsaw in 1945. She went to university and became an internationally successful interior designer. She married Janusz Kosk, an electrical engineer, in 1958. She kept silent for a long time about her experiences as a teenager in various concentration camps. It was not until the 1990s that she began to write down her memories. In 2016, her autobiographical notes were published in German in the book Als Mädchen im KZ Meuselwitz.

(Leipzig Nazi Forced Labour Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Egon Petermann

Registered as a "Gypsy", murdered in Auschwitz

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Egon Petermann was born in Berlin on 28 February 1930. There, the police arrested him on 5 March 1943, and had him deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In August 1944, the SS transferred him to Buchenwald for forced labor. But the 14-year-old boy was too weak for the exhausting work and was put on the list for an extermination transport to Auschwitz on 25 September 1944. Willy Blum and his ten-year-old brother Rudolf were also on this deportation list.

Presumably, Egon Petermann was murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau shortly after his arrival.

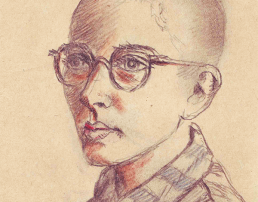

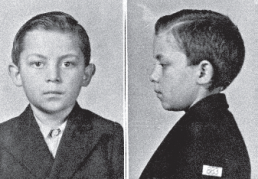

Photograph of Egon Petermann by the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (Racial Hygiene Research Unit), ca. 1940.

Starting in 1937/38, the Reich Health Office had Sinti and Roma summoned by the police so it could perform “racial assessments.” The lists drawn up were later used for deportations to concentration camps.

(Bundesarchiv Berlin)

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Egon Petermann, 3 August 1944.

In the course of the dissolution of the “Gypsy family camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Egon Petermann was transferred to Buchenwald on 3 August. The black stamp in the lower right margin refers to his deportation back to Auschwitz on 26 September 1944.

(Arolsen Archives)

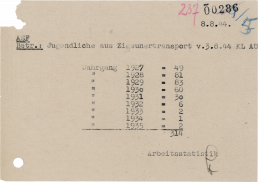

Note from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp labor office, 8 August 1944.

Of 918 Sinti and Roma who arrived from Auschwitz at Buchenwald on 3 August 1944, more than 300 were under the age of 18. Almost all of the older ones were transferred to Mittelbau-Dora. The youngest prisoners remained at Buchenwald. They were returned to Auschwitz a few weeks later, where they were murdered.

(Thür. Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar)

Deportation list for 26 September 1944 from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, 25 September 1944.

Number 88 on the list of 200 persons is the prisoner with the number 74728: Egon Petermann. On the same deportation list was Stefan Jerzy Zweig, whose name had been deleted and replaced by the Sinto Willy Blum.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Siegfried Reinhardt

The erasure of an entire family

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Siegfried Reinhardt was born on 21 January 1926 in Schaffhausen near St. Gallen (Switzerland) and grew up in Munich. His father Rudolf was deemed “unfit for military service” and discharged from the Wehrmacht after the start of the war, then deported to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp. In 1942, he was murdered in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp. The following year, the Munich police arrested Siegfried’s mother and siblings and had them deported to the “Gypsy family camp” Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Siegfried Reinhardt was arrested by the Munich police in 1942 and had to serve a juvenile sentence, after which he was also deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On 17 April 1944, the SS transferred him to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp and from there to the Harzungen subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in mid-May 1944. There, he was assigned to the forced labor tunneling detail. Infirmary files from the Dora camp record him as a patient in March 1945. After that, all trace of the 19-year-old Sinto is lost.

No one from the family of eight survived the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.

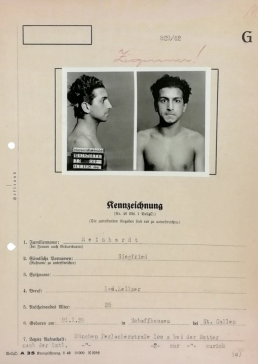

"Gypsy!" Police booking documents for Siegfried Reinhardt, 1942.

In most cases, local authorities and the police were actively involved in enforcing the bans, registering, and arresting Sinti and Roma. In 1942, Siegfried Reinhardt was arrested after skipping school several times. He was sentenced as a juvenile and sent to prison.

(Staatsarchiv München)

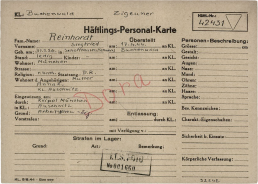

Grounds for imprisonment: "Workshy - Gypsy". Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Siegfried Reinhardt, 17 April 1944.

Siegfried Reinhardt remained in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp for only a few weeks. On 11 May 1944, the SS transferred him to the Harzungen subcamp, which became part of the independent Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in October 1944.

(Arolsen Archives)

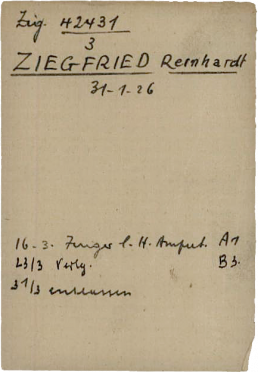

The last trace of Siegfried Reinhardt. Infirmary records from the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, March 1945.

In the file, the first name was incorrectly given as “Ziegfried.” On 16 March, the 19-year-old Siegfried Reinhardt had a finger on his left hand amputated, as can be seen from the document. He was released from the infirmary on 31 March. This is the last trace of the young man.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Franz Rosenbach

From Vienna via Auschwitz to Mittelbau-Dora

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Franz Rosenbach was born on 29 September 1927 in Horaditz (Sudetenland). In February 1943, the Rosenbach family was arrested and imprisoned in Vienna. Deportation to the “Gypsy family camp” Auschwitz-Birkenau followed in 1944. The SS then transferred the 16-year-old Franz Rosenbach to the Mittelbau-Dora subcamp via the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in April 1944. There and in the Harzungen subcamp, he was forced to perform hard labor on construction sites.

In early April 1945, he survived a death march to Dessau. Franz Rosenbach made his way back to his hometown, but found none of his family. It was not until the early 1950s that he was reunited with his sisters Julie and Mizi in Nuremberg. The three were the only family members to survive.

Franz Rosenbach had to fight for decades to obtain German citizenship, which he did not receive until 1991. He was active for many years as deputy chairman for the Bavarian State Association of Sinti and Roma. Franz Rosenbach passed away in 2012 in Nuremberg at the age of 85.

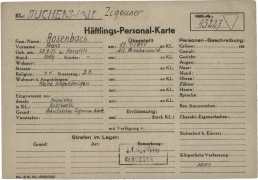

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Franz Rosenbach, 17 April 1944.

The document shows that Franz Rosenbach was arrested by the Vienna police because he was a Gypsy and subsequently deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. In April 1944, he was transferred as a forced laborer to Mittelbau-Dora via the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Arolsen Archives)

Franz Rosenbach recounts his experiences as a teenage forced laborer in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, and Harzungen in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 23 October 1998.

(Visual History Archive)

"If I had not been arrested, if I had learned my profession, today I would have a pension of maybe fifteen hundred euros or two thousand euros. I am on death’s doorstep, to put it plainly. Now I have to scrape together enough to pay for my burial expenses. It's really sad, but it's true."

Struggle for recognition and compensation. Franz Rosenbach in an interview with Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2012.

(Bayerischer Rundfunk)