Jakob Gerste

From Nordhausen to Auschwitz and back again

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Jakob Gerste was born near Gotha on 6 May 1926. The family moved to Nordhausen in the 1930s. In March 1943, he and several siblings were arrested and deported to the “Gypsy family camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where his brothers Rudolf and Heinrich were murdered.

In Auschwitz, Jakob Gerste was assigned to the forced labor bricklaying detail. In April 1944, the SS transferred him via Buchenwald to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, within sight of his hometown Nordhausen. He was assigned to the forced labor construction site detail. He survived and was liberated in Bergen-Belsen in April 1945. He spent the rest of his life in Holzminden (Lower Saxony). Of his family, only he and his sister Emma survived the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.

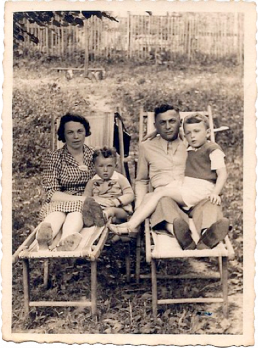

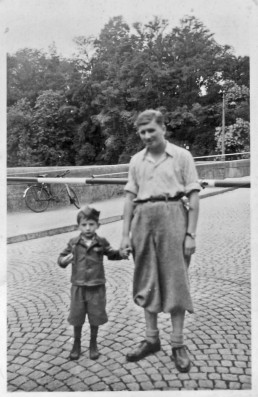

The Gerste family in Nordhausen, around 1938.

From left to right: Anna, Rudolf, Jakob (standing), Hermann, mother Blondine with son Heinrich, Emma and Erwin. At the time this picture was taken, the father Robert Wagner had already been sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg)

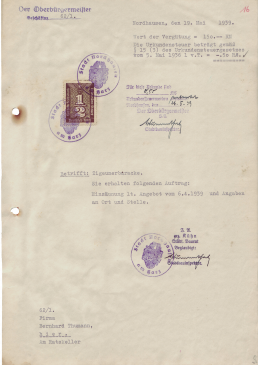

Order from the building authority of the city of Nordhausen to the Bernhard Thumann company to fence in the "Gypsy barracks" at Holungsbügel, 19 May 1939.

In October 1939, a few months after this order for fencing was placed, the Sinti and Roma were forbidden to leave their places of residence. The Gerste family was forced to move their caravan to the fenced-in area next to the “Gypsy barracks” on the outskirts of town.

(Kreisarchiv Nordhausen)

"The Nordhausen Gestapo imprisoned us in March 1943. It was early in the morning. We had to leave everything behind, we could only take what we were wearing with us."

Interview with Jakob Gerste,

17 September 2000.

(Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg)

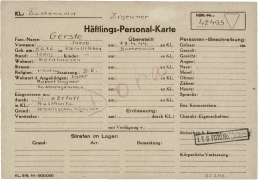

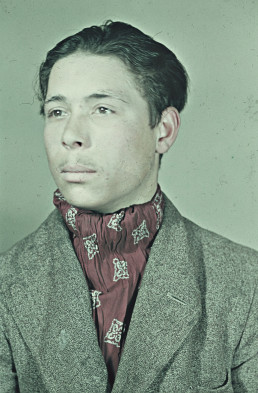

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Jakob Gerste, 17 April 1944.

On 17 April 1944, the SS transferred Jakob Gerste from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald. The place of residence of his father is given as Neuengamme Concentration Camp. The writing in red letters ‘Dora’ refers to the transport to the Mittelbau-Dora camp a few days later. On the card, there is written an incorrect date of birth.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Shraga Milstein (Feliks Milsztajn)

From Poland to Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Feliks Milsztajn was born in 1933 in the Polish town of Piotrków Trybunalski. In October 1939, the German occupiers forced the Jewish family to move into a ghetto. His mother was deported to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in 1944; the SS sent him, his brother, and his father to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in late 1944, where his father died.

In January 1945, the SS transferred Feliks Milsztajn and other children to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. The camp was liberated on 15 April 1945. Later, he learned that his mother had also been deported to Bergen-Belsen. She died shortly after the liberation, without the two of them having seen each other again.

In May 1945, the 12-year-old was able to have his 9-year-old brother, who had been left behind in Buchenwald, brought to Bergen-Belsen. A short time later, the two were sent to a children’s home in Sweden before leaving for Israel in 1948. There, Feliks changed his name to Shraga Milstein and became a teacher and the director of the Massuah Institute for Holocaust Studies. Since 2019, he has been the chair of the advisory board of the Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation.

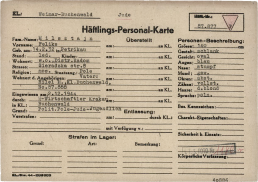

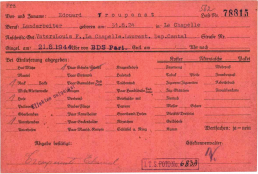

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Feliks Milsztajn (today Shraga Milstein), 2 December 1944.

One month later, the SS transferred Feliks to Bergen-Belsen. On the form, his date of birth is given as 1932 rather than 1933. His father had told the SS that his son was a year older in order to protect him.

(Arolsen Archives)

“In Nov. 1944, we were shipped in a cattle wagon to Germany – my father, brother, and myself to Buchenwald, my mother to Ravensbrück. When we parted at the train station was the last time, I saw her. A few days after our arrival in Buchenwald, my father came back to our barracks in the evening with a stern look in his eyes. He took my brother and me aside and said: "we have to part and we will not see each other anymore. Take care of your younger brother, remember your names and the fact that you have family in Palestine." He gave us a hug and we went to sleep. I later learned that the next day he was killed at the age of 43. All my efforts, during the years, to find out what happened and how he knew his fate, were in vain. A few weeks later, I was transferred with a group of friends my age to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp.”

From Shraga Milstein's Holocaust Remembrance Day speech at United Nations Headquarters in New York, 27 January 2020.

(United Nations)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Joseph Schleifstein

(Szlajfaztajn)

A three-year-old in Buchenwald

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Joseph was born to Israel and Esther Szlajfaztajn on 7 March 1941 in Sandomierz, Poland. At the end of 1942, the German occupiers established a ghetto for Jews in the city, and the family remained there until its dissolution in January 1943. In January 1945, the entire family was deported to the German Reich. Esther was sent to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, and Israel and three-year-old Joseph arrived at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 20 January 1945. With the help of his father and other prisoners, he survived until liberation.

In 1946, Joseph and his father reunited with his mother Esther in Dachau, which was now a DP camp. In 1947, the family emigrated to the USA and built a new life for themselves in New York.

The story of Joseph Schleifstein, who is said to have been smuggled into the Buchenwald camp in a sack, served as the basis for Roberto Benigni’s internationally acclaimed Italian tragicomedy La vita è bella in 1997.

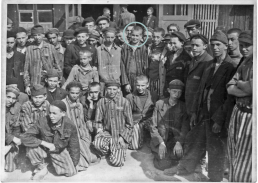

Joseph Schleifstein in a group of children and adolescents from the liberated Buchenwald Concentration Camp in the Rheinfelden quarantine camp in Switzerland, June 1945.

Joseph and other juvenile Buchenwald survivors were taken to Switzerland for recuperation on a Kindertransport (children’s transport). He later rejoined his father.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Naftali Fürst

Deported from Bratislava with his brother

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Schmuel Fürst was born in Bratislava (Slovakia) on 20 February 1931, his brother Naftali on 18 December 1932. The brothers came from a Jewish family. In 1942, they were sent to a forced labor camp in Sered.

In early November 1944, the entire family was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the brothers were separated from their parents. The SS evacuated Auschwitz in January 1945, and 13-year-old Naftali Fürst and his 14-year-old brother were driven on a death march to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. For days, the two traveled in sub-zero temperatures, first on foot, then in an open cattle car. After arriving at Buchenwald, they were placed in Children’s Block 66 in the Little Camp.

Severely ill, Naftali witnessed the liberation of the camp on 11 April 1945. The day before, the SS had sent his brother on a death march that would last for weeks. It was not until 9 May, when he was near death, that he was liberated. In the summer of 1945, the brothers and parents reunited in Bratislava. They later emigrated to Israel.

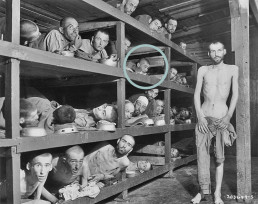

Naftali Fürst in the Little Camp at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 16 April 1945.

After arriving at Buchenwald, Naftali Fürst fell seriously ill and was sent to the infirmary. Shortly after liberation, American war correspondents photographed the emaciated prisoners in the Little Camp. Naftali Fürst recognized himself in this photo.

(Photo: Harry Miller, Buchenwald Memorial)

"Seventy-five years ago, I was a twelve-year-old boy who was liberated in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. I came from Auschwitz - after a death march and a transport in an open wagon in -25° weather. It was January 23, 1945. I am grateful for my great good fortune. I thank all the brave men for liberating 21,000 prisoners who were only skin and bones, including about 900 children."

From Naftali Fürst's speech commemorating the 75th anniversary of the liberation, 11 April 2020.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Alone in the world, without parents, without my brother, without family". Interview with Naftali Fürst about the Buchenwald liberation in April 1945 and the reunion with his family in Bratislava, 26 January 2021.

At first, Naftali Fürst believed that his brother and parents had not survived. In the summer of 1945, the four met again in Bratislava.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Jean Louis Netter

A Jewish schoolboy in the Holzen subcamp

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Jean Louis Netter was born in Paris on 29 August 1928. After the German occupation, he and his family lived in an internment camp for Jews near Toulouse. The Gestapo deported him and his father to Buchenwald in August 1944. His mother and sister were sent to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp.

In the fall of 1944, the SS transferred the 16-year-old Jean Louis and his father to the Holzen subcamp in the Weserbergland region. There, they worked as forced laborers for the armament projects Hecht and Stein. In April 1945, they were driven on a death march to Bergen-Belsen.

With the help of their fellow prisoners, both father and son survived. Jean Louis’ mother died in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in March 1945; his sister was saved by the Swedish Red Cross. After the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp was liberated, Jean Louis Netter returned to France and later became a factory owner in Paris.

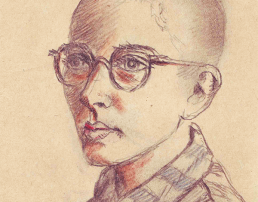

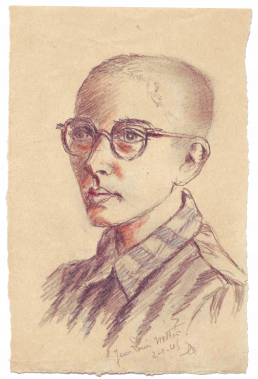

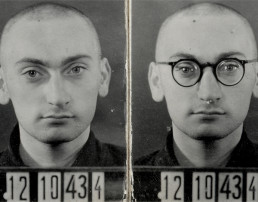

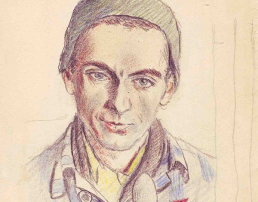

Portrait of Jean Louis Netter, drawn by fellow prisoner Camille Delétang, 2 January 1945.

Camille Delétang secretly drew nearly 200 portraits of prisoners in Holzen in 1944/45. For decades they were thought to be lost, until they turned up in Celle in 2012. They had disappeared in April 1945 during a death march from Holzen to Bergen-Belsen.

(Mittelbau-Dora Memorial)

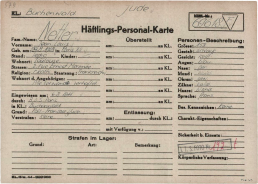

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Jean Louis Netter, 6 August 1944.

The 15-year-old Jean Louis was registered in the Buchenwald camp as “Polit-Franzose, Jude” (French political prisoner, Jew). The entry for the place of residence of his relatives reads: “All relatives arrested.”

(Arolsen Archives)

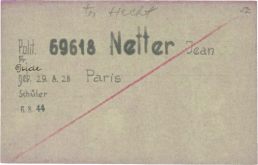

Buchenwald Concentration Camp work card for Jean Louis Netter, 1944.

The handwritten note “tr Hecht” [Transport Hecht] indicates that Netter was assigned to the underground work detail with the codename Hecht, located near Holzen. At the end of 1944, there were about 500 prisoners in the Hecht detail. Jean Louis Netter was the youngest of them.

(Arolsen Archives)

"...when I saw a French prisoner approaching me, he said to me, 'It seems that you need an interpreter for the infirmary.' To my affirmative reply he suggested himself, and I accepted him. He then added with some hesitation [...] that he had his son with him, who was 15 years old. I understood his wish. [...] So Leo Netter became the 'infirmary interpreter' and Jean Louis, his son, became the general dogsbody. This may not have been to everyone's taste, but I was very happy to begin my service by protecting this child from the work details. He would not have survived the hardships that winter brought."

Armand Roux's account of the rescue of Jean-Louis Netter, 1949.

Armand Roux, a French political prisoner, was assigned as a prisoner doctor at the Holzen subcamp in September 1944.

(Armand Roux, Im Zeichen des Zebras, Holzminden 2015)

"Little Netter was transferred to the infirmary, where he was a 'deputy' for the orderly. He survived thanks to the care of Master Homme and Dr. Roux."

Czesław Ostańkowicz’s account of the rescue of Jean Louis Netter in the Holzen subcamp, 1968.

The Polish political prisoner Czesław Ostańkowicz was a block elder in Holzen.

(Czesław Ostańkowicz, Straszna góra Ettersberg, Łódź 1968)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Rolf Kralovitz

As a Hungarian Jew from Leipzig to Buchenwald

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Rolf Kralovitz was born in 1925 and spent his childhood with his parents and his sister Annemarie in Leipzig. From 1935 onwards, his father lived in Hungary. The family was initially spared from the deportation of Jews from Leipzig to ghettos in occupied Eastern Europe, which began in 1942, because they were Hungarian citizens. In October 1943, however, Rolf, his mother, and his sister were arrested by the Gestapo. The mother and sister were deported to Ravensbrück and murdered there. The 18-year-old Rolf was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

There, he was assigned to the bricklayers’ work detail and housed in Block 22 with other Jewish prisoners. He occasionally worked as a hairdresser for the SS and prisoner functionaries. On 11 April 1945, he was liberated.

In May 1945, Rolf Kralovitz returned to Leipzig, then moved to West Germany in 1946 where he became a well-known actor and author. He died in 2015 in Cologne.

Rolf Kralovitz as a 14-year-old (back row, second from left) with friends in the schoolyard of the Carlebach School, 1939.

Because he was forbidden to attend a public school, Rolf Kralovitz attended the Higher Israelite School in Leipzig, run by Ephraim Carlebach, beginning in 1935.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

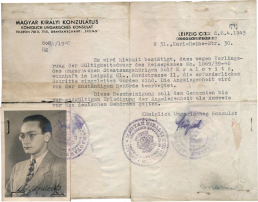

Document certifying Rolf Kralovitz’ Hungarian citizenship, 6 April 1943.

Until the occupation of Hungary by the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) in the spring of 1944, Hungarian citizenship protected Jews from deportation to extermination camps. Max Kralovitz, Rolf’s father, had lived in Hungary since 1935, but was unable to bring his family to join him. In 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

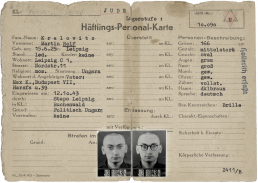

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Rolf Kralovitz, 12 October 1943.

On 12 October 1943, Rolf Kralovitz was registered as a Hungarian Jewish prisoner at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, along with four other male Jews from Leipzig. The stamp Hollerith erfaßt indicates that his data was recorded in a punch card index used to organize the forced labor in the concentration camps.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

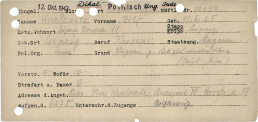

Registry sheet for Rolf Kralovitz from the office at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 12 October 1943.

The handwritten note “Dikal” was Gestapo shorthand for Darf in kein anderes Lager (May not go to any other camp). It was used for Jewish prisoners who were citizens of an allied or neutral country. The Gestapo wanted to retain access to these prisoners and prevent them from being transferred to other camps.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

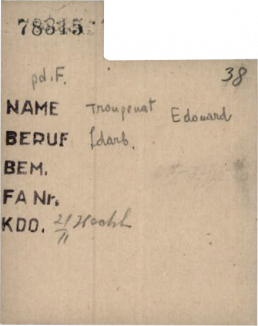

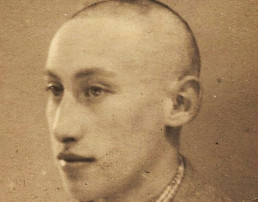

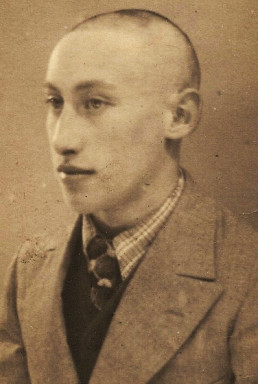

Edouard Troupenat

A resistance fighter deported to Buchenwald

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Edouard Troupenat was born on 31 August 1924 in La Chapelle, a small village in the French Alps. He was one of three sons of the farmer Louis Henri Troupenat and his wife Agathe. After leaving school, Edourd Troupenat became a farm laborer.

In 1943, at the age of 18, he joined the Résistance and participated in underground military actions against the German occupiers. In May 1944, the German field gendarmerie arrested him. In mid-August, he was deported from the Compiègne camp near Paris to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. From there, the SS transferred him to the Holzen subcamp (southern Lower Saxony) in September 1944, where he was a forced laborer in an underground facility of the Volkswagen company.

In April 1945, he survived a death march from Holzen to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, but died there on 5 May 1945, three weeks after it was liberated by British troops. He was 20 years old.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Erich Davidsohn

As a young "special operation Jew" in Buchenwald

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Erich Davidsohn was born in Hanover in 1922. He was the only child of Richard and Elfriede Davidsohn. He grew up in Salzhemmendorf, a village near Hamelin, in Lower Saxony. The Davidsohns looked after the small synagogue. They and one other family were the only Jews in the village. In 1935, Erich began an apprenticeship in his father’s butcher shop.

In the early morning hours of 10 November 1938, SA men ransacked the local synagogue and destroyed the interior. Erich Davidsohn and his father were taken into Schutzhaft (lit. “protective custody,” but actually preventive detention) and sent from the Hamelin penitentiary to Buchenwald. There, their heads were shaved, and they faced beatings and hunger on a daily basis.

In early December 1938, the SS released the 16-year-old Erich Davidsohn from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, presumably because of his age. His father was released a few days later. On 6 February 1939, Erich was able to emigrate to England. His father, mother, and cousin emigrated to Argentina.

Erich (left) with his mother Elfriede, his father Robert Davidsohn, and his cousin Juliane Guttmann in Hanover, 1939.

As early as 1935, Robert Davidsohn began preparations for his family’s emigration to South America. But it was not until 16 June 1939, a few months after his return from Buchenwald, that he succeeded in getting himself, his wife, and his niece Juliane to Buenos Aires. Erich Davidsohn left for England in February 1939. His mother had registered him for a Kindertransport (children’s transport) while he was being held at Buchenwald. He never saw his parents again.

(private property/Mel Davidsohn)

"After the first week names were called and releases started. On the morning of 6 December my name was called. You had to rush to the gate or miss being released. A quick farewell with my father and I was away. We had to stand in line near the offices all day and not move. No food was given and, worst of all, we couldn’t go to the toilet. We were then given money for the rail fare and were bussed to the station. Several of us got on the train direct to Hanover and we arrived in the middle of the night. The other people on the train kept well away from us, possibly because they knew who we were and where we had been. And, of course, we were very dirty and literally stank."

Erich Davidsohn on his release from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, after 1939.

(https://pogrome1938-niedersachsen.de/salzhemmendorf/)

Stolperstein in Salzhemmendorf for Erich Davidsohn, 7 March 2020.

Since 1995, Cologne based artist Gunter Demnig has been commemorating the victims of the Nazi regime with his project Stolpersteine – Stumbling Stones. All over Germany, the artist lays small brass memorial stones in sidewalks in front of buildings where individuals who were persecuted and murdered by the Nazi regime lived or worked.

(CC)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Lower Saxony Memorial Foundation, November Pogrom 1938 in Lower Saxony:

stiftung-ng.de/…/-pogrom-1938-in-lower-saxony/

Novemberpogrome 1938 in Niedersachsen, Salzhemmendorf:

pogrome1938-niedersachsen.de.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Kurt Ansin

A Sinto from Magdeburg

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Kurt Ansin was born on 2 October 1921. He grew up in Magdeburg. Beginning in the mid-1930s, the Sinti living there were banned from all public places and placed under constant police surveillance. The Ansin family was forced to move to the Holzweg “Gypsy camp” in 1938.

In the course of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich), Kurt Ansin and his father were arrested in June 1938 and sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, where his father died. Kurt Ansin was released in 1939 and returned to Magdeburg. In 1943, however, he was arrested again and deported with his family to the “Gypsy family camp” at Auschwitz-Birkenau. From there, the SS transferred him via Buchenwald to the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in 1944.

Kurt Ansin survived, but almost all of his relatives were murdered. He married and had eight children. In 1984, at the age of only 61, he died of the physical and psychological conditions that were direct consequences of his time in the camp.

Kurt Ansin, February 1940.

Employees of the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (Racial Hygiene Research Unit) under the direction of Robert Ritter and Eva Justin took this photo of Kurt Ansin in the Magdeburg forced labor camp. Shortly before, the Magdeburg police had registered all Sinti as alleged criminals and created a “Gypsy file.”

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Kurt Ansin (right) at the age of 15 with a friend, 1937.

Until 1938, Kurt Ansin lived with his family in Dessau-Roßlau. He was one of the few of the Sinti minority there who survived. His friend next to him, who was the same age, was murdered in Auschwitz, as were his siblings.

(Hanns Weltzel/ University of Liverpool Library)

The Gypsy Camp at Großer Silberberg in Magdeburg.

In May 1935, the city of Magdeburg established the Gypsy Camp Magdeburg Holzweg, to which Kurt Ansin, along with the other Sinti from Anhalt, was sent shortly before his arrest in 1938. In the camp, the Sinti lived under miserable conditions and constant police surveillance.

(Stadtarchiv Magdeburg)

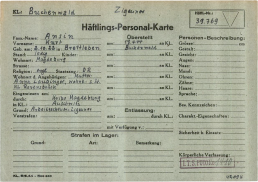

From Auschwitz back to Buchenwald. Kurt Ansin’s prisoner registration file, 17 April 1944.

In April 1944, the SS once again sent Kurt Ansin from Auschwitz to Buchenwald and shortly thereafter to the Ellrich-Juliushütte and Harzungen subcamps. There, he was assigned to the brutal construction forced labor detail.

(Arolsen Archives)

Nothing found.

"My grandfather was the only survivor of eleven siblings. Only his mom and he were left. You have to imagine that: They really wanted to wipe us out. My grandfather was later a broken and ruined man. But we are a very proud people. So, my grandfather's goal was to rebuild a big clan - that we might become many again."

Report by Janko Lauenberger about his grandfather Kurt Ansin, August 2012.

Kurt Ansin, his mother Anna Donna Ansin, and Adelheid Krause were the only three survivors of the Magdeburg Gypsy Camp. Despite this, he was initially not recognized in the GDR as a victim of the Nazi regime. His grandson recalls the family history.

(TAZ)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.