Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Labor re-education camps (Arbeitserziehungslager, AEL) served as punishment for civilian workers, especially foreign laborers, who were accused of refusing to work. The temporary “disciplinary labor” was intended to instill a work ethic.

Between April 1941 and March 1944, almost 2,000 boys and men were sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp as labor re-education prisoners. The SS released most of them after three to eight weeks. Some, however, did not survive the hard forced labor.

Beginning in November 1942, nearly all prisoners in the Buchenwald AEL were children and adolescents from the Soviet Union sent there by the Gestapo. The juvenile labor re-education prisoners were housed together in Block 8, later known as the Children’s Block. From mid-1943 onwards, no AEL prisoners were released. Almost all of them remained as concentration camp prisoners at Buchenwald.

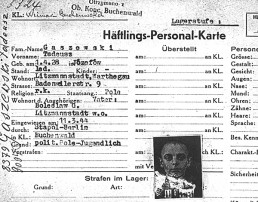

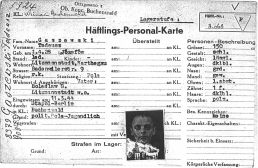

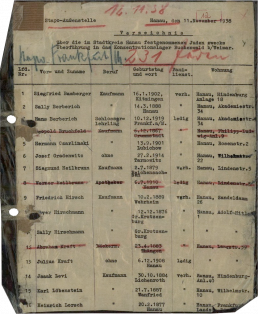

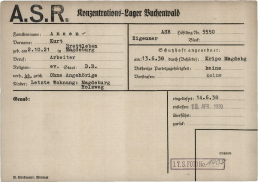

Personal effects file for Wasil Sawtschuk, 13 August 1942.

On 13 August 1942, the Halle State Police delivered 12-year-old Wasil Sawtschuk (Sowtschuk in some documents) to the Buchenwald labor re-education camp. Ten weeks later he was released and transferred back to prison in Halle. Wasil Sawtschuk was one of the youngest labor re-education prisoners at Buchenwald.

(Arolsen Archives)

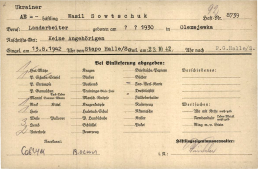

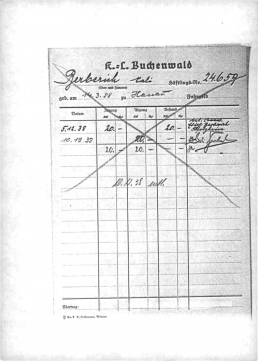

From the Buchenwald Concentration Camp file on Tadeusz Gaszewski, 11 March 1944.

The Gestapo sent Tadeusz Gaszewski, a schoolboy from Litzmannstadt (Łódź), to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 11 March 1944. He was the last person to be admitted as a labor re-education prisoner.

(Arolsen Archives)

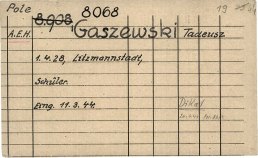

From the Buchenwald Concentration Camp file on Tadeus Gaszweski, 11 March 1944.

Tadeusz Gaszewski was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp as a labor re-education prisoner. However, the SS registered him as a prisoner in the category “political Pole – juvenile.” It is not known if Tadeusz Gaszewski survived.

(Arolsen Archives)

Forced labor in the armaments factory. Buchenwald railroad siding at the Gustloff Plant II, 1943.

In 1942, construction of the Gustloff Plant II began at Buchenwald. After its completion, the SS’s interest in labor re-education prisoners declined, since the plant used primarily concentration camp inmates for its workforce. In 1943, the Gestapo established a central AEL for Thuringia at Röhmhild in the Thuringian Forest. Almost all prisoners sent to the Buchenwald AEL were juveniles. They had to work in the particularly difficult excavation and construction details on the premises of the Gustloff Plant II or in railroad construction. Many of them died.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"In the Construction Detail I we had 250 young people, citizens of the Soviet Union, Poland and Jews. We were looking for ways to save the young people from perishing. [...] About 150 teenagers had to carry bricks from the storage area, where the bricks were stored, about 2000 m to the Gustloff Plant II construction sites (hall construction).

The first day they carried 2 bricks on their shoulders, in their hands or arms. The second day, SS-Scharführer Schmidt’s overseers at the storage area forced them to carry 4 bricks. The SS Scharführer started yelling like rabid dogs: Carry the bricks faster, pick them up faster, run faster! And he ran alongside them for a few hundred meters. They beat the boys, making them fall down, dropping the stones in fear. The result was that broken bricks were brought to the construction site."

Report by Ernst Plaschke on the AEL prisoners as forced laborers in Buchenwald, April 1979.

Unskilled juvenile AEL prisoners had to perform particularly hard forced labor. Ernst Plaschke was Kapo of Construction Detail I in Buchenwald. After his liberation, the former political prisoner described the conditions under which the young people had to haul bricks to the Gustloff Plant II construction site.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Lebendiges Museum Online: Arbeitserziehungslager im Deutschen Reich. Deutsches Historisches Museum

dhm.de.

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Limited shelter: The children's blocks 8 and 66

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children’s block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943. In the Little Camp, Barracks 66 served as a children’s block from January 1945 onwards.

Most of the children in these blocks were between 14 and 17 years old. They did not have to work, but they received only half of the already meager food rations. Hunger was omnipresent, but until mid-1944 it was possible to organize secret classes and small cultural events.

Despite all the efforts of the political prisoner functionaries to prevent it, the SS repeatedly sent children on extermination transports to Auschwitz and other death camps. On 10 April 1945, the SS entered the Little Camp and dispatched many minors on death marches. When the camp was liberated on the next day, there were 900 children and adolescents still alive. At least 1600 had died.

"[...] as we stood outside at roll call in the biting cold and deep snow, the block elder informed us that all children up to the age of 16 should report to him for transfer to a children's block. After a short break, panic suddenly broke out. We all suspected a ruse. The children had seen enough, everyone thought it was a trick to finish us off [...]. Of course, most of them reported for transport right away, for almost all of them it was a fateful decision. Very few of them survived. After my experiences in Buchenwald, I had the feeling that the block elder could be trusted."

Report by Robert J. Büchler, 1994.

Robert J. Büchler (1929-2009) was persecuted as a Jew, and the SS deported him from Auschwitz to Buchenwald in January 1945 at the age of 16. Fellow prisoners housed him in the Children’s Block 66 of the Little Camp. One day before liberation, the SS sent him on a death march from which he was able to flee.

(Robert J. Büchler, “Am Ende des Weges. Kinderblock 66 im Konzentrationslager Buchenwald,” in: Dachauer Hefte 6, 1994).

Antonín Kalina (front right) in front of Block 66 in the Little Camp, after 11 April 1945.

Beginning in late 1944, the Czech Communist Antonín Kalina (1902-1990) was the block elder responsible for the children and teenagers in Block 66. He used his contacts with the camp resistance and changed the names of Jewish children in early April 1945 to protect them from the death marches. Public recognition for the man deported to Buchenwald in 1939 did not come until after his death. In 2012, he was honored by the Yad Vashem memorial as a Righteous Among the Nations.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

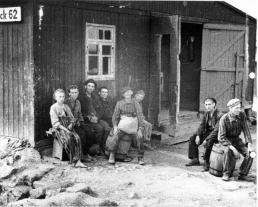

Liberated teenagers sitting in front of Block 62 in the Little Camp, between 11 and 15 April 1945.

In 1944/45, the Little Camp, where conditions were even worse than in the main camp, housed a particularly large number of children and teenagers. They had come to Buchenwald with transports from the evacuated camps in the east, including Auschwitz.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

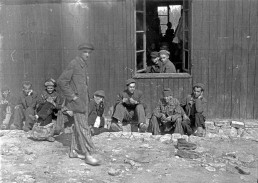

Liberated teenagers in front of Children’s Block 66, after 11 April 1945.

Children’s Block 66, which was built by prisoner functionaries, saved many children and adolescents from deportation to forced labor in subcamps and certain death. In the children’s block, the young people were also better protected from being assaulted by fellow adult prisoners.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Abandoned housing in Children’s Block 66 of the Little Camp, April/May 1945.

The primitive three-level wooden platforms used as beds were typical for the wooden barracks in the Little Camp. Shortly before liberation, the SS drove many prisoners on death marches. The barracks were searched and destroyed when they searched for Jewish prisoners.

(Photo: Alfred Stüber, Buchenwald Memorial)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail, launched a rescue initiative for young Polish prisoners in the fall of 1939. They convinced the SS of the idea of an apprentice masonry detail. The bricklayers’ school was intended to protect the minors from the exhausting forced labor in other work details.

In the spring of 1942, other political prisoners who were prisoner functionaries succeeded in setting up the Poles’ School. Under the pretext of having to overcome language difficulties in the labor details, they organized German lessons for the boys. The Poles’ School was also meant to protect them from the exhausting forced labor.

The bricklayers’ and Poles’ schools increased the chances of survival in the camp, especially for Polish, and later also for Jewish, children and teenagers.

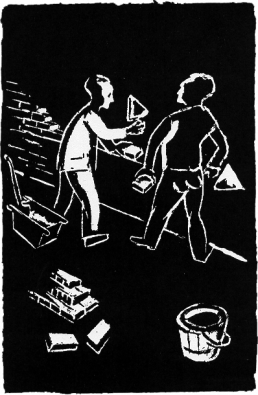

Rescue by the bricklayers’ Detail. Woodcut Durch Arbeit from the series "A Friendship" by Herbert Sandberg, 1947/49

The German graphic artist, cartoonist, and resistance fighter Herbert Sandberg (1908-1991) endured ten years of imprisonment, the last seven in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. In April 1944, while in Buchenwald, he drew a series of sketches recounting his journey since he was first incarcerated in July 1938. He worked with stove soot and whiting on paper and linen remnants. Sandberg was trained as a bricklayer in a group of Jewish prisoners in 1941 – this saved him, as a “useful worker,” from deportation to Auschwitz. After liberation, he published the drawings he made in Buchenwald in a collection of his works.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"The communists in the prisoner self-administration obtained [...] permission from the SS to set up a bricklayers’ school by claiming there was a shortage of skilled workers for camp construction. Officially, the school was intended to train new workers for the construction detail, so it was supervised by that detail and the teacher was the Kapo of the Kommando Maurer Truppengarage (garage bricklayers) detail, Robert Siewert. [...] It was in this school that we survived the first Thuringian winter."

Report by Władysław Kożdoń, 2006.

Polish Boy Scout Władysław Kożdoń (1922-2017) was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in October 1939, shortly after his 17th birthday, and was sent to the bricklayers’ school.

(Władysław Kożdoń, „…ich kann dich nicht vergessen“. Erinnerungen an Buchenwald, Göttingen 2007)

Robert Siewert (left) in conversation with the "Buchenwald child" Stefan Jerzy Zweig uand Bruno Apitz (right) in Weimar, 9 February 1964.

Robert Siewert (1887-1973) used his position as Kapo of a construction detail to initiate the bricklaying school. In 1945 he became Minister of Interior Affairs in Saxony-Anhalt, but lost this post in 1950 as part of Stalinist purges within the SED. He later worked in the GDR’s Ministry of Construction.

(Photo: Friedrich Gahlbeck, Bundesarchiv)

"We learned new vocabulary in German and had to repeat it several times. In class we dealt with grammar, spelling and reading. We also wrote dictations. We wrote on slates with styluses, read from the blackboard and from some books. There weren’t many books. We put sentences together, and the advanced students wrote summaries in German in their notebooks."

Włodzimierz Kuliński's recollections of lessons at the Polish School, undated.

Włodzimierz Kuliński was deported from Poland to Buchenwald when he was 15 years old. German lessons were given by two Polish prisoners. On 29 November 1941, the young Polish teacher Henryk Sokolak was appointed head of the Polish School with the support of the camp elder Ernst Busse. Due to the boys’ different levels of education, Sokolak divided them into two groups so that he could teach them better.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as "special operation Jews”

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps. Some of the nearly 10,000 men deported to Buchenwald were teenagers.

The camp was ill-prepared to receive 10,000 new prisoners. The Jewish prisoners were placed in improvised housing, and were subjected to humiliation, harassment and violence. Several prisoners were murdered by the SS or died as a result of prison conditions. Most of the survivors, including almost all of the young people, were released after a few weeks. The goal of the Nazi regime was still to convince German Jews to emigrate by using violence and terror.

Onlookers in front of the burning synagogue in Gottschedstraße in Leipzig, 10 November 1938.

In November 1938, the National Socialists burned down synagogues throughout the German Reich. They invaded the homes and businesses of Jews and mistreated the residents. In many cases, a mob of onlookers gathered in front of the synagogues.

The excuse for the pogroms was the attack by a German-Polish Jew on a German diplomat in Paris. The state-organized terror marked the transition from the rejection and exclusion of Jews to their systematic and violent persecution.

(Sächsisches Staatsarchiv)

"So I came to school with my bicycle and wanted to put it in the cellar. And someone came to meet me and said, 'There's no school today, the synagogues are burning.' And then I rode off on my bicycle to Gottschedstraße. And there I saw the big synagogue burning. A few hundred meters further, the big Orthodox synagogue [...] Then I rode through the city. And there I saw all kinds of Jewish stores, where the shards of glass lay on the sidewalk, where the goods had been torn out of the shop windows. On Augustusplatz I saw the large clothing store Bamberger & Herz burning. It was terrible. The whole city was full of glass shards. At Brühl too, for example. Brühl was famous for its international fur trade, which was very much in Jewish hands. And there too very much was ruined and very much was broken by the SA."

"Today there’s no school, the synagogues are burning." Recollection by Rolf Kralovitz of the November 1938 pogrom in Leipzig, interview from 2008.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

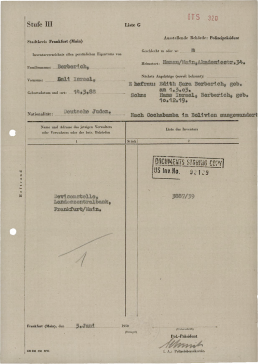

Document issued by the Frankfurt (Main) police department concerning the fate of the Berberich family, 3 June 1950.

According to the document, Sally and Edith Berberich emigrated with their son Hans to Cochabamba in Bolivia. Even in this postwar document, the names Israel and Sara remain added to their actual names, a convention forced upon the Jews by the Nazis in 1938.

The November pogroms of 1938 triggered a wave of emigration. Between then and the beginning of the war, about 120,000 Jews left the German Reich. They had to leave their property behind.

(Arolsen Archives)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

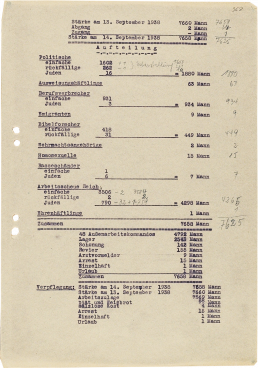

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social elements”), the police sent over 10,000 men and several hundred women to the camps – most of them were adults, but some were teenagers. About 4,000 men were sent to Buchenwald, including about 1,200 Jews. For a brief time, the majority of prisoners in the camp were those with a black triangle identification badge, which marked prisoners as “anti-social”.

All those who were not a part of the “national community”, such as the unemployed, beggars, vagrants and those persecuted as gypsies, were considered “anti-social” or “alien to the community.” The police worked closely with the labor and welfare offices during the waves of arrests.

It was not until 2020 that the Bundestag (German parliament) recognized those persecuted as anti-social as victims of the Nazi regime.

"They called them work-shy. We are forbidden to talk to them. Mostly they are people with physical or mental disabilities who are taught to work here in the camp. They get the black mark. [...] Young people with spindly legs are supposed to learn how to work here under the supervision of the SS, who are fed to the hilt. [...] The accommodation of the "work-shy" is nothing more than a disgrace itself. From one day to the next they built a large barracks below the other barracks, with next to nothing in it. That’s how they live and they die en masse."

Report by the political prisoner Moritz Zahnwetzer on the arrival at Buchenwald of those arrested in the 1938 Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich, 1946.

(Moritz Zahnwetzer: KZ Buchenwald. Erlebnisbericht Kassel 1946)

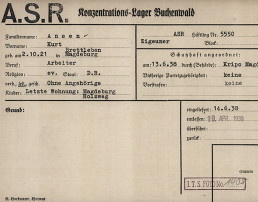

Kurt Ansin’s prisoner ID, 1938.

Kurt Ansin was arrested at age 16 for being a gypsy and sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in June 1938. His file was stamped by the SS with the abbreviation “A.S.R.” (Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich). Kurt Ansin had to wear the black triangle designating him as anti-social on his prison uniform.

(Arolsen Archives)

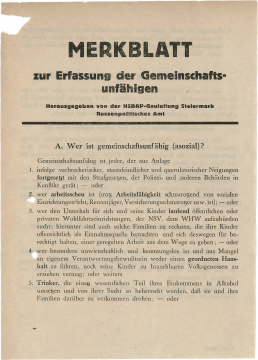

"Guidelines for the Registration of those Unfit for the Community," Office of Racial Policy Styria, December 1942.

The Volksgemeinschaft ideology was not only racist, but also included the idea of achievement. People without work were considered unworthy and seen as ballast, and were therefore to be disciplined through forced labor. The idea of “unfit for the community” was interpreted very broadly.

(Landesarchiv Steiermark)

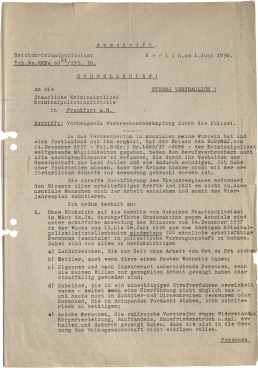

"Crime Prevention Measures.” Decree from Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo, Security Police) and head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service) to police commissioners, 1 June 1938.

The incarceration of those arrested on grounds of being anti-social in concentration camps took place in two waves in 1938. The decree of 1 June 1938 propelled the second wave of arrests later that month.

(StA Marburg)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

The Camp

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

In July 1937, the first prisoners arrived at Ettersberg near Weimar. The SS forced them to build a concentration camp for 8,000 male prisoners. Both political opponents of the regime and those persecuted for racial and social reasons were to be interned there.

By the end of the war, the Buchenwald Concentration Camp had developed into the center of a complex camp system with a total of 139 subcamps, where prisoners served as forced laborers for the armaments industry. In total, around 280,000 people were imprisoned at Buchenwald, and more than 56,000 died.

Not only men, but also women, teenagers and children were imprisoned in Buchenwald and its satellite camps. Children were in particular danger. Because they were unable to work, they had hardly any chance of survival. To protect them from forced labor and deportation to certain death, political prisoners built shelters for children and adolescents in selected barracks.

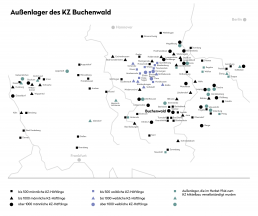

Beyond the main camp: A dense network of subcamps.

Most of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp’s subcamps camps were established after 1942, the turning point of the war after the Battle of Stalingrad. Prisoners were used for cleanup work in the cities and for forced labor in the armaments industry.

(Studio IT’S ABOUT)

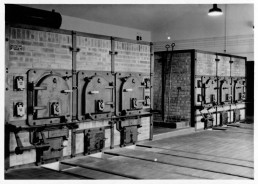

Interior of the crematorium at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1943.

Before 1940, the deaths of prisoners from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp were registered and their bodies cremated at the municipal crematorium in Weimar. In order to conceal the increasing number of prisoners murdered at the camp, a separate crematorium was built on camp premises in the summer of 1940. The incinerators were made by the Erfurt company Topf & Sons, which also manufactured the incinerators for the Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

The photo is from an album that camp commandant Hermann Pister had created for representational purposes.

(Musée de la Résistance et de la Deportation)

Children of SS members pose in front of a toy cannon in the Führersiedlung at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1943.

The SS barracks and housing estates were located only a few meters from the camp on the Ettersberg. SS officers and their families lived in the Führersiedlung.

(Photo: Georges Angéli, Buchenwald Memorial)

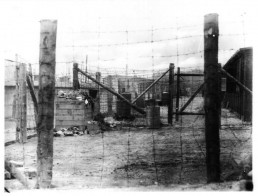

Camp road and barracks in the Little Camp, after liberation, April/May 1945.

In the Little Camp, which was established in 1942 as a quarantine zone for prisoners arriving on the mass transports, conditions were catastrophic. From 1944 onwards it was permanently overcrowded; starvation and death were ever-present. Political prisoners managed to establish a place of refuge for children, most of them Jewish, in Block 66 of the Little Camp.

(Photo: Alfred Stüber, private property)

Jurek Kestenberg on his memories of Buchenwald in an interview with David P. Boder, Fontenay-aux-Roses (France), 31 July 1946.

Jurek Kestenberg was born in Poland in 1929. He and his parents were deported from the Warsaw Ghetto to Majdanek in 1943. In August 1944 he was sent to Buchenwald. He survived thanks to the help of fellow prisoners. After liberation, he traveled to France on a children’s transport in June 1945, where Boder interviewed him in Yiddish.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation, Historical Overview of the History of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1937-1945: buchenwald.de/en

Förderverein Buchenwald e.V.: „Buchenwald war überall – die Errichtung eines Netzwerkes der Außenlager“:

aussenlager.buchenwald.de.

“Gedenksteine Buchenwaldbahn. Ein Projekt der Initiative “Gedenkweg Buchenwaldbahn”:

gedenksteine-buchenwaldbahn.de.

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social…

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as “special operation Jews”

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail

Limited shelter: The children’s blocks 8 and 66

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children's block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.