Naftali Fürst

Deported from Bratislava with his brother

zugang

Schmuel Fürst was born in Bratislava (Slovakia) on 20 February 1931, his brother Naftali on 18 December 1932. The brothers came from a Jewish family. In 1942, they were sent to a forced labor camp in Sered.

In early November 1944, the entire family was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the brothers were separated from their parents. The SS evacuated Auschwitz in January 1945, and 13-year-old Naftali Fürst and his 14-year-old brother were driven on a death march to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. For days, the two traveled in sub-zero temperatures, first on foot, then in an open cattle car. After arriving at Buchenwald, they were placed in Children’s Block 66 in the Little Camp.

Severely ill, Naftali witnessed the liberation of the camp on 11 April 1945. The day before, the SS had sent his brother on a death march that would last for weeks. It was not until 9 May, when he was near death, that he was liberated. In the summer of 1945, the brothers and parents reunited in Bratislava. They later emigrated to Israel.

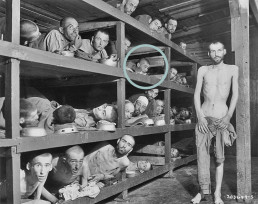

Naftali Fürst in the Little Camp at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 16 April 1945.

After arriving at Buchenwald, Naftali Fürst fell seriously ill and was sent to the infirmary. Shortly after liberation, American war correspondents photographed the emaciated prisoners in the Little Camp. Naftali Fürst recognized himself in this photo.

(Photo: Harry Miller, Buchenwald Memorial)

"Seventy-five years ago, I was a twelve-year-old boy who was liberated in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. I came from Auschwitz - after a death march and a transport in an open wagon in -25° weather. It was January 23, 1945. I am grateful for my great good fortune. I thank all the brave men for liberating 21,000 prisoners who were only skin and bones, including about 900 children."

From Naftali Fürst's speech commemorating the 75th anniversary of the liberation, 11 April 2020.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Alone in the world, without parents, without my brother, without family". Interview with Naftali Fürst about the Buchenwald liberation in April 1945 and the reunion with his family in Bratislava, 26 January 2021.

At first, Naftali Fürst believed that his brother and parents had not survived. In the summer of 1945, the four met again in Bratislava.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Limited shelter: The children's blocks 8 and 66

zugang

Children were particularly vulnerable to the dangers of the camp. To protect them, political prisoner functionaries set up a children’s block in Block 8 of the main camp in July 1943. In the Little Camp, Barracks 66 served as a children’s block from January 1945 onwards.

Most of the children in these blocks were between 14 and 17 years old. They did not have to work, but they received only half of the already meager food rations. Hunger was omnipresent, but until mid-1944 it was possible to organize secret classes and small cultural events.

Despite all the efforts of the political prisoner functionaries to prevent it, the SS repeatedly sent children on extermination transports to Auschwitz and other death camps. On 10 April 1945, the SS entered the Little Camp and dispatched many minors on death marches. When the camp was liberated on the next day, there were 900 children and adolescents still alive. At least 1600 had died.

"[...] as we stood outside at roll call in the biting cold and deep snow, the block elder informed us that all children up to the age of 16 should report to him for transfer to a children's block. After a short break, panic suddenly broke out. We all suspected a ruse. The children had seen enough, everyone thought it was a trick to finish us off [...]. Of course, most of them reported for transport right away, for almost all of them it was a fateful decision. Very few of them survived. After my experiences in Buchenwald, I had the feeling that the block elder could be trusted."

Report by Robert J. Büchler, 1994.

Robert J. Büchler (1929-2009) was persecuted as a Jew, and the SS deported him from Auschwitz to Buchenwald in January 1945 at the age of 16. Fellow prisoners housed him in the Children’s Block 66 of the Little Camp. One day before liberation, the SS sent him on a death march from which he was able to flee.

(Robert J. Büchler, “Am Ende des Weges. Kinderblock 66 im Konzentrationslager Buchenwald,” in: Dachauer Hefte 6, 1994).

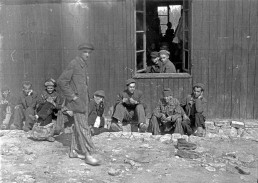

Antonín Kalina (front right) in front of Block 66 in the Little Camp, after 11 April 1945.

Beginning in late 1944, the Czech Communist Antonín Kalina (1902-1990) was the block elder responsible for the children and teenagers in Block 66. He used his contacts with the camp resistance and changed the names of Jewish children in early April 1945 to protect them from the death marches. Public recognition for the man deported to Buchenwald in 1939 did not come until after his death. In 2012, he was honored by the Yad Vashem memorial as a Righteous Among the Nations.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

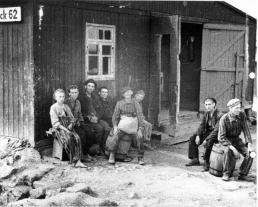

Liberated teenagers sitting in front of Block 62 in the Little Camp, between 11 and 15 April 1945.

In 1944/45, the Little Camp, where conditions were even worse than in the main camp, housed a particularly large number of children and teenagers. They had come to Buchenwald with transports from the evacuated camps in the east, including Auschwitz.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

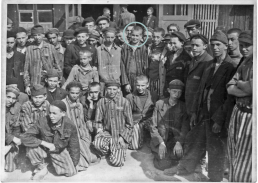

Liberated teenagers in front of Children’s Block 66, after 11 April 1945.

Children’s Block 66, which was built by prisoner functionaries, saved many children and adolescents from deportation to forced labor in subcamps and certain death. In the children’s block, the young people were also better protected from being assaulted by fellow adult prisoners.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Abandoned housing in Children’s Block 66 of the Little Camp, April/May 1945.

The primitive three-level wooden platforms used as beds were typical for the wooden barracks in the Little Camp. Shortly before liberation, the SS drove many prisoners on death marches. The barracks were searched and destroyed when they searched for Jewish prisoners.

(Photo: Alfred Stüber, Buchenwald Memorial)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.

Jean Louis Netter

A Jewish schoolboy in the Holzen subcamp

zugang

Jean Louis Netter was born in Paris on 29 August 1928. After the German occupation, he and his family lived in an internment camp for Jews near Toulouse. The Gestapo deported him and his father to Buchenwald in August 1944. His mother and sister were sent to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp.

In the fall of 1944, the SS transferred the 16-year-old Jean Louis and his father to the Holzen subcamp in the Weserbergland region. There, they worked as forced laborers for the armament projects Hecht and Stein. In April 1945, they were driven on a death march to Bergen-Belsen.

With the help of their fellow prisoners, both father and son survived. Jean Louis’ mother died in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in March 1945; his sister was saved by the Swedish Red Cross. After the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp was liberated, Jean Louis Netter returned to France and later became a factory owner in Paris.

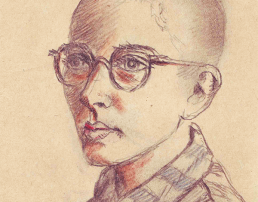

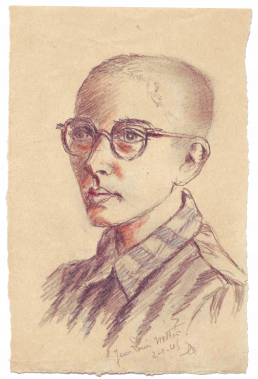

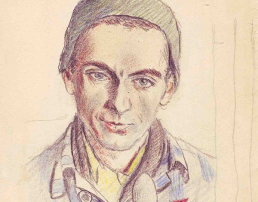

Portrait of Jean Louis Netter, drawn by fellow prisoner Camille Delétang, 2 January 1945.

Camille Delétang secretly drew nearly 200 portraits of prisoners in Holzen in 1944/45. For decades they were thought to be lost, until they turned up in Celle in 2012. They had disappeared in April 1945 during a death march from Holzen to Bergen-Belsen.

(Mittelbau-Dora Memorial)

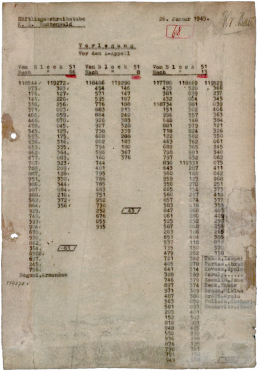

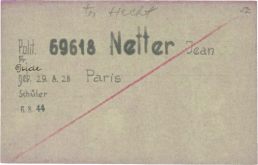

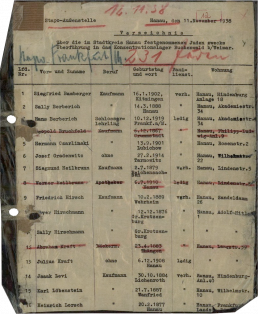

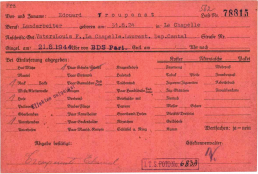

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Jean Louis Netter, 6 August 1944.

The 15-year-old Jean Louis was registered in the Buchenwald camp as “Polit-Franzose, Jude” (French political prisoner, Jew). The entry for the place of residence of his relatives reads: “All relatives arrested.”

(Arolsen Archives)

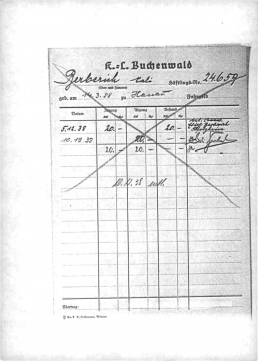

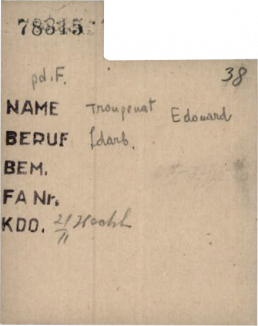

Buchenwald Concentration Camp work card for Jean Louis Netter, 1944.

The handwritten note “tr Hecht” [Transport Hecht] indicates that Netter was assigned to the underground work detail with the codename Hecht, located near Holzen. At the end of 1944, there were about 500 prisoners in the Hecht detail. Jean Louis Netter was the youngest of them.

(Arolsen Archives)

"...when I saw a French prisoner approaching me, he said to me, 'It seems that you need an interpreter for the infirmary.' To my affirmative reply he suggested himself, and I accepted him. He then added with some hesitation [...] that he had his son with him, who was 15 years old. I understood his wish. [...] So Leo Netter became the 'infirmary interpreter' and Jean Louis, his son, became the general dogsbody. This may not have been to everyone's taste, but I was very happy to begin my service by protecting this child from the work details. He would not have survived the hardships that winter brought."

Armand Roux's account of the rescue of Jean-Louis Netter, 1949.

Armand Roux, a French political prisoner, was assigned as a prisoner doctor at the Holzen subcamp in September 1944.

(Armand Roux, Im Zeichen des Zebras, Holzminden 2015)

"Little Netter was transferred to the infirmary, where he was a 'deputy' for the orderly. He survived thanks to the care of Master Homme and Dr. Roux."

Czesław Ostańkowicz’s account of the rescue of Jean Louis Netter in the Holzen subcamp, 1968.

The Polish political prisoner Czesław Ostańkowicz was a block elder in Holzen.

(Czesław Ostańkowicz, Straszna góra Ettersberg, Łódź 1968)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Rolf Kralovitz

As a Hungarian Jew from Leipzig to Buchenwald

zugang

Rolf Kralovitz was born in 1925 and spent his childhood with his parents and his sister Annemarie in Leipzig. From 1935 onwards, his father lived in Hungary. The family was initially spared from the deportation of Jews from Leipzig to ghettos in occupied Eastern Europe, which began in 1942, because they were Hungarian citizens. In October 1943, however, Rolf, his mother, and his sister were arrested by the Gestapo. The mother and sister were deported to Ravensbrück and murdered there. The 18-year-old Rolf was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

There, he was assigned to the bricklayers’ work detail and housed in Block 22 with other Jewish prisoners. He occasionally worked as a hairdresser for the SS and prisoner functionaries. On 11 April 1945, he was liberated.

In May 1945, Rolf Kralovitz returned to Leipzig, then moved to West Germany in 1946 where he became a well-known actor and author. He died in 2015 in Cologne.

Rolf Kralovitz as a 14-year-old (back row, second from left) with friends in the schoolyard of the Carlebach School, 1939.

Because he was forbidden to attend a public school, Rolf Kralovitz attended the Higher Israelite School in Leipzig, run by Ephraim Carlebach, beginning in 1935.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

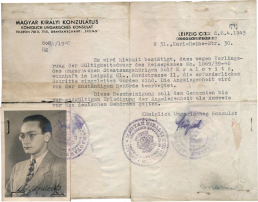

Document certifying Rolf Kralovitz’ Hungarian citizenship, 6 April 1943.

Until the occupation of Hungary by the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) in the spring of 1944, Hungarian citizenship protected Jews from deportation to extermination camps. Max Kralovitz, Rolf’s father, had lived in Hungary since 1935, but was unable to bring his family to join him. In 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

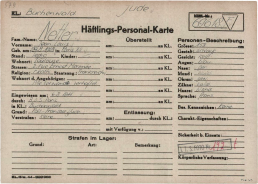

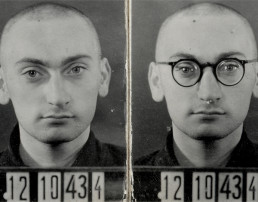

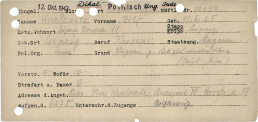

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Rolf Kralovitz, 12 October 1943.

On 12 October 1943, Rolf Kralovitz was registered as a Hungarian Jewish prisoner at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, along with four other male Jews from Leipzig. The stamp Hollerith erfaßt indicates that his data was recorded in a punch card index used to organize the forced labor in the concentration camps.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

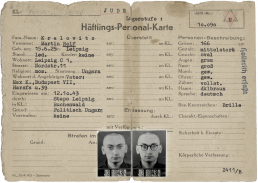

Registry sheet for Rolf Kralovitz from the office at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 12 October 1943.

The handwritten note “Dikal” was Gestapo shorthand for Darf in kein anderes Lager (May not go to any other camp). It was used for Jewish prisoners who were citizens of an allied or neutral country. The Gestapo wanted to retain access to these prisoners and prevent them from being transferred to other camps.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Rescue Initiatives: Bricklayers’ school and Poles’ school

zugang

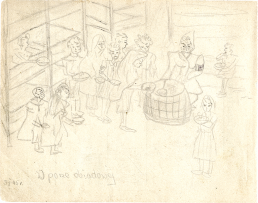

Under the pretext of training skilled workers for the German war effort, prisoner functionaries around Robert Siewert, a political prisoner and Kapo of the construction detail, launched a rescue initiative for young Polish prisoners in the fall of 1939. They convinced the SS of the idea of an apprentice masonry detail. The bricklayers’ school was intended to protect the minors from the exhausting forced labor in other work details.

In the spring of 1942, other political prisoners who were prisoner functionaries succeeded in setting up the Poles’ School. Under the pretext of having to overcome language difficulties in the labor details, they organized German lessons for the boys. The Poles’ School was also meant to protect them from the exhausting forced labor.

The bricklayers’ and Poles’ schools increased the chances of survival in the camp, especially for Polish, and later also for Jewish, children and teenagers.

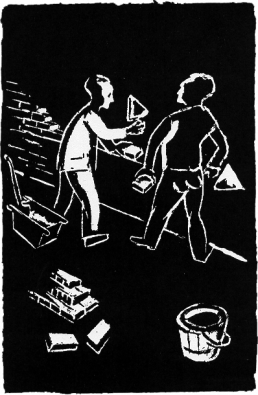

Rescue by the bricklayers’ Detail. Woodcut Durch Arbeit from the series "A Friendship" by Herbert Sandberg, 1947/49

The German graphic artist, cartoonist, and resistance fighter Herbert Sandberg (1908-1991) endured ten years of imprisonment, the last seven in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. In April 1944, while in Buchenwald, he drew a series of sketches recounting his journey since he was first incarcerated in July 1938. He worked with stove soot and whiting on paper and linen remnants. Sandberg was trained as a bricklayer in a group of Jewish prisoners in 1941 – this saved him, as a “useful worker,” from deportation to Auschwitz. After liberation, he published the drawings he made in Buchenwald in a collection of his works.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"The communists in the prisoner self-administration obtained [...] permission from the SS to set up a bricklayers’ school by claiming there was a shortage of skilled workers for camp construction. Officially, the school was intended to train new workers for the construction detail, so it was supervised by that detail and the teacher was the Kapo of the Kommando Maurer Truppengarage (garage bricklayers) detail, Robert Siewert. [...] It was in this school that we survived the first Thuringian winter."

Report by Władysław Kożdoń, 2006.

Polish Boy Scout Władysław Kożdoń (1922-2017) was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in October 1939, shortly after his 17th birthday, and was sent to the bricklayers’ school.

(Władysław Kożdoń, „…ich kann dich nicht vergessen“. Erinnerungen an Buchenwald, Göttingen 2007)

Robert Siewert (left) in conversation with the "Buchenwald child" Stefan Jerzy Zweig uand Bruno Apitz (right) in Weimar, 9 February 1964.

Robert Siewert (1887-1973) used his position as Kapo of a construction detail to initiate the bricklaying school. In 1945 he became Minister of Interior Affairs in Saxony-Anhalt, but lost this post in 1950 as part of Stalinist purges within the SED. He later worked in the GDR’s Ministry of Construction.

(Photo: Friedrich Gahlbeck, Bundesarchiv)

"We learned new vocabulary in German and had to repeat it several times. In class we dealt with grammar, spelling and reading. We also wrote dictations. We wrote on slates with styluses, read from the blackboard and from some books. There weren’t many books. We put sentences together, and the advanced students wrote summaries in German in their notebooks."

Włodzimierz Kuliński's recollections of lessons at the Polish School, undated.

Włodzimierz Kuliński was deported from Poland to Buchenwald when he was 15 years old. German lessons were given by two Polish prisoners. On 29 November 1941, the young Polish teacher Henryk Sokolak was appointed head of the Polish School with the support of the camp elder Ernst Busse. Due to the boys’ different levels of education, Sokolak divided them into two groups so that he could teach them better.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.

VIOLENCE

HUNGER

ILLNESS

DEATH

All contact with the camp SS was marked by violence. Hunger was a constant companion of the children and adolescents in the concentration camp. The catastrophic hygienic conditions led to an accumulation of diseases from which there was hardly any protection.

The children and adolescents lived in constant fear of death. They watched many people, including friends and relatives, die. Not only were they backward in their physical development due to hunger and diseases, they were also robbed of their childhood.

Gert Silberbard in an interview with David P. Boder in Geneva, August 27, 1946.

At the age of 16, Gert Silberbard was deported from Auschwitz to Buchenwald. In 1946, he vividly recalled being deprived of food and water after arriving at the Little Camp.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

MEALS FOR AN ENTIRE WORKDAY

8 a.m. - First breakfast

1 glass of hot milk with butter and honey

Roll with butter and ham

Roll with honey

Roll with jam or with something else

11 o'clock - Second breakfast

Pancakes with ham and scrambled eggs, rolled in breadcrumbs and fried in butter

Noodles au gratin with eggs, honey

and melted butter with rice fritters

Noodles with apples, butter and rolls

2 o'clock - Lunch

Clear soup (barley soup) made of chicken broth and breadcrumbs

or with fat dumplings

Stuffed beef with potatoes and paprika sauce

Italian pasta casserole with smoked sausage and tomatoes

Pierogi with liver

Dessert of semolina pudding with vanilla sauce

Fruit dessert, pudding from millet groats with jam

A glass of eggnog

17 o'clock - Supper

Asparagus in tomato sauce

Cauliflower fritters

Spätzle with butter and rolls

Stuffed peppers with tomato sauce

Potato pancakes with cream

The menu is unfinished. THERE’S AN ALARM AGAIN!

Dream menu for a whole working day by Maria Brzęcka, December 1944.

Maria Brzęcka, then 14 years old, put together her dream menu for when she was freed from the Meuselwitz labor camp. However, she could not remember the taste of most of the dishes and asked the women in her quarters to describe them to her. She couldn’t finish her list because of an air raid alert.

(Als Mädchen im KZ Meuselwitz. Erinnerungen von Maria Brzęcka-Kosk, Dresden 2016)

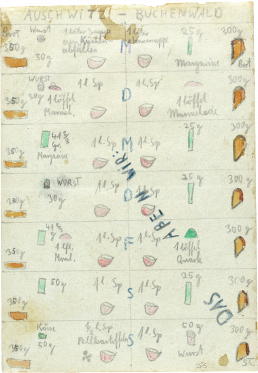

"This is what we ate." Drawing by Thomas Geve, 1945.

In his drawing, the 16-year-old compared the food rations in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, where he was liberated on 11 April 1945.

(Yad Vashem)

"So we handled heavy, toxic raw materials, picked everything up without protective gloves, no protective masks or aprons were required for us, we breathed in all the poisons and stood up to our knees in saltpeter. The locals called us "lemons" because our skin was so discolored."

Éva Pusztai-Fahidi recalls the deadly working conditions, 2011.

Éva Fahidi, who was deported from Hungary as a teenager, was a forced laborer in the Münchmühle subcamp. The working conditions in the munitions factory were murderous, and the prisoners could not protect themselves from hazardous substances because there was no protective clothing for them.

(Éva Fahidi, The Soul of Things, University of Toronto Press, 2020)

Plaster fresco from a barracks in the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp, made by Tanguy Tolila-Croissant in the fall of 1944.

Tanguy Tolila-Croissant was born in Paris on 16 October 1925. He began studying art at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Paris in 1942. In June 1944, he was arrested for resisting the German occupiers and deported to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in August, then to Ellrich-Juliushütte. There, he frescoed the walls in his block. Many similar pictures created by him have survived from the time before his arrest – with one difference: never is a dead tree to be seen. Tolila-Croissant died on 30 December 1944, at the age of 19.

(German Historical Museum)

Realms of Experience

Nothing found.

Return home

zugang

The liberated children and adolescents wanted nothing more than to return home to their families. For many survivors, however, that was impossible. Jewish survivors had often lost all their relatives in the Holocaust, and their hometowns had been obliterated. Reports of pogroms in Poland and Eastern Europe discouraged people from returning.

Many of the children and young people did not know where their relatives were or whether they were still alive. The Allies and aid organizations such as the Red Cross helped to reunite families.

Those who were able to return home the quickest were the young people from Western Europe who had been deported to the camps as political prisoners. Many were back with their families by early May 1945. They were considered heroes of the Résistance and were received with public honors in their home communities.

"By mid-May [1945], most of the prisoners whose health had been restored had left for their home countries. But there were exceptions: the Spaniards whom Franco had turned over to the Nazis preferred to remain in exile rather than return to a country still in the hands of a dictator. Many of the Poles were uncertain about the policies and new borders of their reborn state and therefore wanted to wait for further developments. Surviving Jews from Poland, Hungary and Romania feared returning to countries whose recent past had been marked by the horrific consequences of anti-Semitism."

Thomas Geve on the problems of returning home after liberation, 2000.

In his autobiographical account, Thomas Geve describes the impossibilities of returning home, especially for Eastern European Jews.

(Thomas Geve, Aufbrüche. Weiterleben nach Auschwitz, Constance 2000)

Western European prisoners leaving Bergen-Hohne barracks by truck, 25 April 1945.

In April 1945, evacuation transports from Mittelbau-Dora were sent to the Bergen-Hohne barracks, part of the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp complex. British troops liberated the survivors on 15 April 1945. Ten days later, the first liberated prisoners from France, Belgium and the Netherlands were able to return home.

(IWM)

Roger De Coster on the day after his return to his hometown near Antwerp, 29 April 1945.

Roger De Coster was deported in 1944 at the age of 16 as a political prisoner to Buchenwald and from there to Mittelbau-Dora, together with his older brothers and his father. He was one of the liberated prisoners who started their return journey home from Bergen-Hohne on 25 April 1945. The day after his return home, he had himself photographed with numerous bouquets of flowers that had been presented to him on his return.

(Private property De Coster family)

"Saturday we were welcomed everywhere in Belgium. We arrived in Mol about four o'clock in the afternoon, where they took very good care of us. I left there with the Persoons family, who had come to pick up Jules Persoons, and arrived home around midnight, where everyone was waiting impatiently for Daddy, Willy, François, and me. The reunion was, of course, very emotional for me, and it was very joyful. I asked about Daddy and Willy [...]. Eight days later, I learned that my father had died on May 2 in a hospital in Weimar. François was still alive. He arrived in Paris and was home on June 9. I was the first from my village to return, but eight days later I got typhoid fever and just barely escaped death. Fortunately, after a few weeks I was back on my feet and a new life began for me."

Roger De Coster's account of his return home on 28 April 1945, c. 1991.

(François and Roger De Coster, Van Breendonk naar Ellrich-Dora, Berchem 2006).

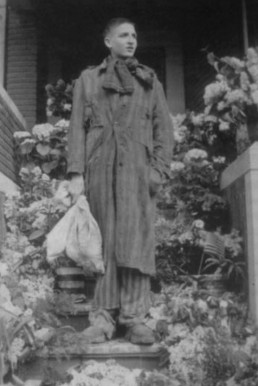

Return of a Nacht-und-Nebel prisoner. Charles Brusselairs in prisoner's clothing after liberation, 1945/46.

Charles Brusselairs was arrested in 1943 at the age of 18 for resisting the German occupiers in Belgium. He was deported to Germany on the basis of the clandestine Nacht-und-Nebel-Erlass (Night-and-Fog directive). After spending time in various prisons, he arrived at Buchenwald in February 1945. The SS drove him on a death march to Theresienstadt in early April. There, he was liberated four weeks later by Soviet soldiers. After months in sanatoriums, he returned to his family in Belgium in 1946.

(Private property)

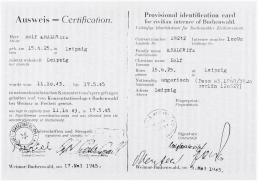

Rolf Kralovitz’ provisional identity card, 5 and 17 May 1945.

The US Army issued Rolf Kralovitz a provisional identity card in Buchenwald. On 17 May 17, he was officially released and could return to his hometown of Leipzig. The document also noted the time of his imprisonment in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

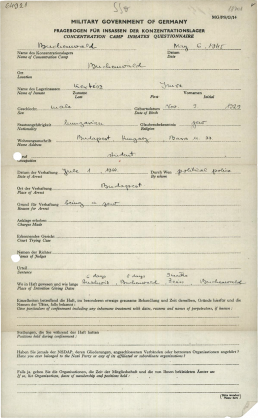

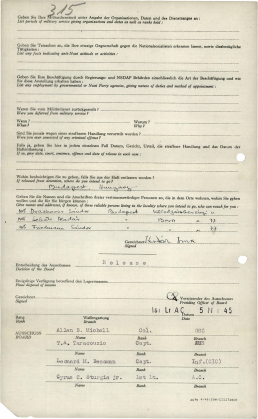

Questionnaire for concentration camp prisoners, filled out by Imre Kertész, 6 May 1945.

Imre Kerstész was born in Budapest (Hungary) in 1929. In July 1944, the police arrested him, and he was deported to Buchenwald via Auschwitz. After his liberation by the US Army, he filled out a questionnaire. As the reason for his imprisonment, he succinctly noted “being a Jew.” Another question asked, “Where do you intend to go if you are released from prison?” The 15-year-old entered “Budapest, Hungary”.

(Arolsen Archives)

"After a few steps I recognized our building. [...] On our floor, I rang our doorbell. [...] The door opened a crack, and a yellow, bony face of a strange middle-aged woman looked at me. She asked who I was looking for, and I said to her that I lived here. 'No,' she said, 'this is where we live,' and was about to close the door again, but she couldn't because I had put my foot in the door. I tried to explain to her that it was a mistake, because it was from here that I had left [...]."

In his story, the future Nobel laureate in Literature described his autobiographically-inspired protagonist's return home to Budapest and the conflicts it entailed, 1975.

(Imre Kertész, Fatelessness)

After liberation

Nothing found.

1938: Deported to Buchenwald as "special operation Jews”

zugang

In the course of the November pogroms of 1938, the Gestapo sent 30,000 Jews, designated by the SS as “special operation Jews,” to concentration camps. Some of the nearly 10,000 men deported to Buchenwald were teenagers.

The camp was ill-prepared to receive 10,000 new prisoners. The Jewish prisoners were placed in improvised housing, and were subjected to humiliation, harassment and violence. Several prisoners were murdered by the SS or died as a result of prison conditions. Most of the survivors, including almost all of the young people, were released after a few weeks. The goal of the Nazi regime was still to convince German Jews to emigrate by using violence and terror.

Onlookers in front of the burning synagogue in Gottschedstraße in Leipzig, 10 November 1938.

In November 1938, the National Socialists burned down synagogues throughout the German Reich. They invaded the homes and businesses of Jews and mistreated the residents. In many cases, a mob of onlookers gathered in front of the synagogues.

The excuse for the pogroms was the attack by a German-Polish Jew on a German diplomat in Paris. The state-organized terror marked the transition from the rejection and exclusion of Jews to their systematic and violent persecution.

(Sächsisches Staatsarchiv)

"So I came to school with my bicycle and wanted to put it in the cellar. And someone came to meet me and said, 'There's no school today, the synagogues are burning.' And then I rode off on my bicycle to Gottschedstraße. And there I saw the big synagogue burning. A few hundred meters further, the big Orthodox synagogue [...] Then I rode through the city. And there I saw all kinds of Jewish stores, where the shards of glass lay on the sidewalk, where the goods had been torn out of the shop windows. On Augustusplatz I saw the large clothing store Bamberger & Herz burning. It was terrible. The whole city was full of glass shards. At Brühl too, for example. Brühl was famous for its international fur trade, which was very much in Jewish hands. And there too very much was ruined and very much was broken by the SA."

"Today there’s no school, the synagogues are burning." Recollection by Rolf Kralovitz of the November 1938 pogrom in Leipzig, interview from 2008.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

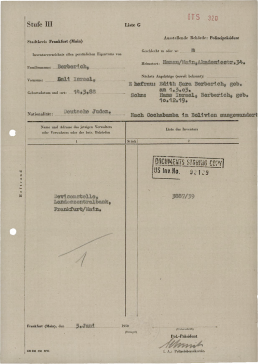

Document issued by the Frankfurt (Main) police department concerning the fate of the Berberich family, 3 June 1950.

According to the document, Sally and Edith Berberich emigrated with their son Hans to Cochabamba in Bolivia. Even in this postwar document, the names Israel and Sara remain added to their actual names, a convention forced upon the Jews by the Nazis in 1938.

The November pogroms of 1938 triggered a wave of emigration. Between then and the beginning of the war, about 120,000 Jews left the German Reich. They had to leave their property behind.

(Arolsen Archives)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.

Life in the liberated camp

zugang

Many liberated prisoners were in a deplorable condition. Some were more dead than alive. Despite self-sacrificing help from US medics and civilian helpers, hundreds of people still died from the effects of imprisonment in Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora in the weeks after liberation. Some were unable to digest the fatty foods they had been given by the helpers.

At Buchenwald, the US troops moved the 900 or so liberated children and young people from the filthy camp barracks to better accommodations, many of them to the former SS buildings. International relief organizations and the US Army organized aid for the young survivors. The US military Rabbi Herschel Schacter stayed in the camp for months to care for the orphans and provide pastoral support.

The International Red Cross delivers medicine to the liberated Buchenwald camp, 17-18 April 1945.

In the first days after the liberation, there was an acute shortage of medical supplies. The seriously ill and starving children were supplied with medicine and food by the International Red Cross.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

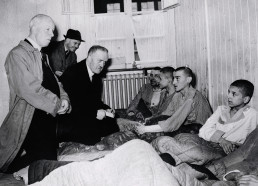

American congressmen visit liberated prisoners in the former camp brothel, which was converted into a hospital ward, 21 April 1945.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"At the time this unit took over the camp there were an estimated 21,000 prisoners there. The greatest problem facing the unit was one of sanitation. The water supply had been cut off due to the destruction of one of the mains by explosives. Latrine facilities in the camp were virtually non-existent and hygiene of any kind was apparently unknown. Prisoners' barracks were in the worst possible condition. Lighting was inadequate, barracks were filthy, barracks overcrowded, inmates underfed and underclothed. Upon taking over the camp, the unit began delousing and cleaning buildings which had formerly housed SS guards. As these buildings were cleared, the worst cases were transferred."

Excerpt from the report of the 120th US Evacuation Hospital, 10 June 1945.

The US liberators wrote a report on the disastrous sanitary conditions in the camp. They set up an emergency hospital.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

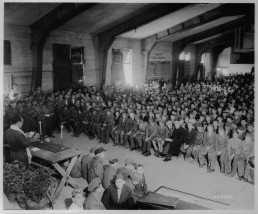

Jewish service in the cinema barracks at Buchenwald, 18 May 1945.

The US military chaplain Rabbi Herschel Schacter arrived at Buchenwald with the 3rd US Army on 11 April 1945, and remained there until June. He was especially committed to the Jewish orphans. The photo was taken at one of the services. The boy sitting in the front row with shorts is Robert Buechler. Sitting in front of the lectern, looking at the camera, is six-year-old Stefan Jakubowicz.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"He arrived at Buchenwald as the first Jew, the Rabbi Schacter. He made ... it was the time of Passover or something. He distributed matzos, and he held services."

Jurek Kestenberg, in an interview with David P. Boder, recalls a service with Rabbi Schacter, 31 July 1946.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute for Technology)

"From floor to ceiling were hundreds upon hundreds of men and very few boys who were strewn over scraggly straw sacks looking down at me, looking down at me out of dazed eyes. [...] I remember their eyes, looking down, looking out of big, big eyes - that's all I saw were eyes - haunted, crippled, paralyzed with fear. They were emaciated skin and bones, half-crazed, more dead than alive. And there I stood and shouted in Yiddish "Sholem Aleychem, Yiden, yir zent frey!" "You are free." The more brave among them slowly began to approach me [...], to touch my Army uniform, to examine the Jewish chaplain's insignia, incredulously asking me again and again, "Is this true? Is it over?"

“You are free!” Report by Rabbi Herschel Schacter, 1981.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Survivors of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in a sanatorium in Sülzhayn (Harz Mountains), 29 June 1945.

The Americans brought several hundred survivors from the Mittelbau Concentration Camps to two sanatoriums in the spa town of Sülzhayn near Ellrich for recuperation. There, nurses from UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) cared for them.

(Photo: Edward Vetrone, NARA)

Liberations

Nothing found.

Edouard Troupenat

A resistance fighter deported to Buchenwald

zugang

Edouard Troupenat was born on 31 August 1924 in La Chapelle, a small village in the French Alps. He was one of three sons of the farmer Louis Henri Troupenat and his wife Agathe. After leaving school, Edourd Troupenat became a farm laborer.

In 1943, at the age of 18, he joined the Résistance and participated in underground military actions against the German occupiers. In May 1944, the German field gendarmerie arrested him. In mid-August, he was deported from the Compiègne camp near Paris to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. From there, the SS transferred him to the Holzen subcamp (southern Lower Saxony) in September 1944, where he was a forced laborer in an underground facility of the Volkswagen company.

In April 1945, he survived a death march from Holzen to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, but died there on 5 May 1945, three weeks after it was liberated by British troops. He was 20 years old.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.