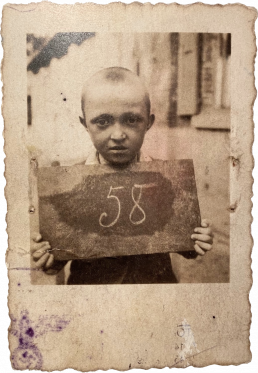

Egon Petermann

Registered as a "Gypsy", murdered in Auschwitz

zugang

Egon Petermann was born in Berlin on 28 February 1930. There, the police arrested him on 5 March 1943, and had him deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In August 1944, the SS transferred him to Buchenwald for forced labor. But the 14-year-old boy was too weak for the exhausting work and was put on the list for an extermination transport to Auschwitz on 25 September 1944. Willy Blum and his ten-year-old brother Rudolf were also on this deportation list.

Presumably, Egon Petermann was murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau shortly after his arrival.

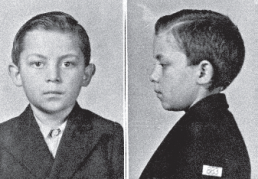

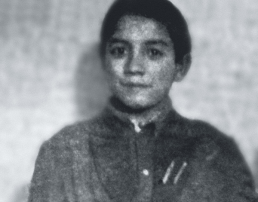

Photograph of Egon Petermann by the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (Racial Hygiene Research Unit), ca. 1940.

Starting in 1937/38, the Reich Health Office had Sinti and Roma summoned by the police so it could perform “racial assessments.” The lists drawn up were later used for deportations to concentration camps.

(Bundesarchiv Berlin)

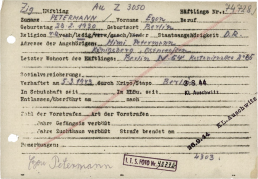

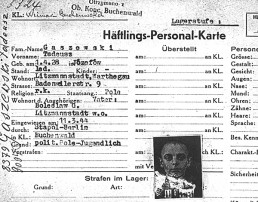

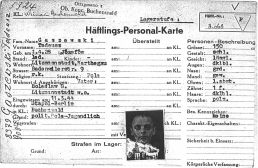

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Egon Petermann, 3 August 1944.

In the course of the dissolution of the “Gypsy family camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Egon Petermann was transferred to Buchenwald on 3 August. The black stamp in the lower right margin refers to his deportation back to Auschwitz on 26 September 1944.

(Arolsen Archives)

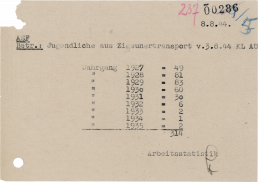

Note from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp labor office, 8 August 1944.

Of 918 Sinti and Roma who arrived from Auschwitz at Buchenwald on 3 August 1944, more than 300 were under the age of 18. Almost all of the older ones were transferred to Mittelbau-Dora. The youngest prisoners remained at Buchenwald. They were returned to Auschwitz a few weeks later, where they were murdered.

(Thür. Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar)

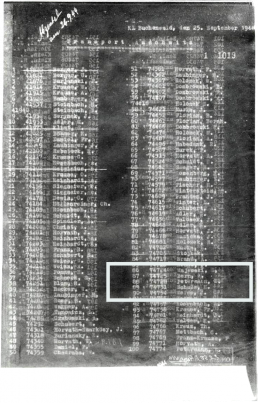

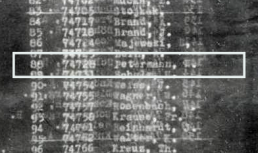

Deportation list for 26 September 1944 from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, 25 September 1944.

Number 88 on the list of 200 persons is the prisoner with the number 74728: Egon Petermann. On the same deportation list was Stefan Jerzy Zweig, whose name had been deleted and replaced by the Sinto Willy Blum.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Living on with no childhood?

CHILD SURVIVORS AS ACTORS IN THE CULTURE OF REMEMBRANCE

In the early postwar period, the children and young people who had been liberated in 1945 from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp and its numerous subcamps became known as the Buchenwald Boys. But by the 1950s, public interest in their stories had ebbed.

For a long time, child survivors were not perceived as a specific group of survivors. Only in the last 20 years have those liberated as children or adolescents received greater attention – partly because there are hardly any survivors left who were liberated as adults.

After years of negotiations, Germany finally recognized Jewish Child Survivors (born in or after 1928) as a victim group in 2014. The recognition entitles them to compensation payments for the trauma experienced in their childhood and youth.

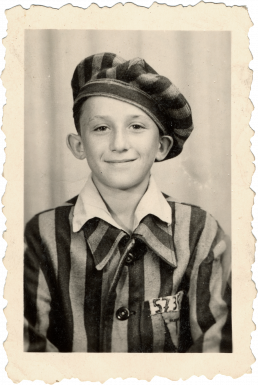

Early signs of remembrance: Liberated "Buchenwald Boys" have their pictures taken in Paris, wearing a prisoner uniform, July 1945.

For the young people, the shared memory of their experiences in the concentration camp was important for the processing of their experiences. The three Jewish boys liberated in Buchenwald, Benek Wrzonski (left), Heniek Kaliksztajn (center) and Zelig Ellenbogen (right), were on the Children’s Relief Transport to France on 8 June 1945. In Paris, they and other Buchenwald Boys went to a photo studio to have their photographs taken, all in the same prisoner uniform. The uniform probably belonged to Mozes Kuznitz.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

"The experiences of my youth are irrevocable and absolute. The world cannot give me back what it has taken from me. I have lost my beloved mother. I have lost almost every member of my family. And I have lost almost every friend and acquaintance of my childhood days. I lost my native language and the ability to believe in anything or trust anyone, and for many years I had lost myself, my own identity."

"Lost my own identity". Report by Thomas Geve, 2000.

The existential experiences of loss in his childhood shaped the life of Thomas Geve. Born Stefan Cohn in Stettin in 1929, he emigrated to Israel after his liberation in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Thomas Geve, Aufbrüche. Weiterleben nach Auschwitz, Constance 2000)

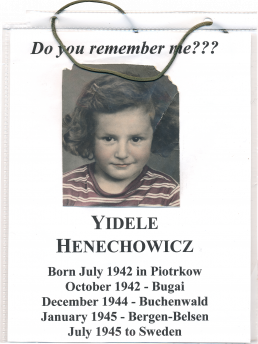

"Do you remember me?" Lanyard worn by Julius Maslovat, 2010.

Julius Maslovat, born Yidele Henechowicz, was transferred from Buchenwald to Bergen-Belsen in January 1945, where he was liberated in April 1945 at the age of barely three. Orphaned, he grew up in Finland with adoptive parents and for decades knew little about his origins. In search of information, he wore this sign in 2010 at the commemoration of the 65th anniversary of the camp liberation in Bergen-Belsen.

(Private property, Julius Maslovat)

Julius Maslovat (l) and Shraga Milstein (r) at the exhibition "Children in Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp," April 2018.

Both had been sent from Buchenwald to Bergen-Belsen in the same transport in January 1945 and met again for the first time in 2018.

(Photo: Diana Gring, Bergen-Belsen Memorial)

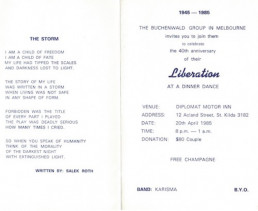

"FREE CHAMPAGNE." Invitation of the Buchenwald Group in Melbourne to the 40th anniversary of the liberation of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1985.

Many of the children and young people liberated in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1945 emigrated to Australia. Since the 1950s, they have celebrated Liberation Day with a festive ball.

(private / Monach University Melbourne)

Child Survivor or Child of Survivors? Estare Weiser (née Kurz), 1946 (left) and 2021 (right).

Estare Kurz was born on 13 April 1945, in the HASAG Leipzig subcamp. Her parents emigrated to the United States in 1951 with their six-year-old daughter. She grew up in Brooklyn.

(private property)

"Even though I didn't have a normal childhood in some ways, I still had a childhood. So, I don't think of myself as a child survivor. You can call me that, but I see myself much more as the child of survivors."

Estare Weiser (née Kurz) in an interview, 26 January 2021.

(FSU Jena)

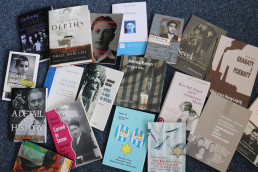

Books by Child Survivors of the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camps (selection), 2021.

Since the 1990s, accounts by child and adolescent survivors have been published in greater numbers. Only at an advanced age did many survivors find the courage and strength to write about their concentration camp experiences. Moreover, as the years passed, the public’s willingness to listen to them increased.

(Photo: Stefan Lochner, Buchenwald Memorial)

“The Jewish memory of the camps will be more long-lived, will be much more permanent. This for the simple reason: because there were deported Jewish children, thousands and tens of thousands, while there were no deported children from the political resistance. [...] In this sense, a great responsibility falls on the Jewish memory in the future. For it will become the preserver and custodian of all experiences of annihilation: first, of course, of its own Jewish experience. But then also all the other experiences: those of the Sinti and Roma [...] those of the political opponents of the Hitler regime, German Communists, Social and Christian Democrats; finally, those of the resistance fighters from the anti-fascist guerrilla movements throughout Europe.”

"A great responsibility." Speech by Jorge Semprún on the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp at the German National Theater in Weimar, 10 April 2005.

The Spanish writer urged the Jewish Child Survivors to preserve the legacy of the politically persecuted, most of whom were elderly. Jorge Semprún died in 2011 at the age of 87. He had survived Buchenwald as a political prisoner.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Siegfried Reinhardt

The erasure of an entire family

zugang

Siegfried Reinhardt was born on 21 January 1926 in Schaffhausen near St. Gallen (Switzerland) and grew up in Munich. His father Rudolf was deemed “unfit for military service” and discharged from the Wehrmacht after the start of the war, then deported to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp. In 1942, he was murdered in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp. The following year, the Munich police arrested Siegfried’s mother and siblings and had them deported to the “Gypsy family camp” Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Siegfried Reinhardt was arrested by the Munich police in 1942 and had to serve a juvenile sentence, after which he was also deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On 17 April 1944, the SS transferred him to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp and from there to the Harzungen subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in mid-May 1944. There, he was assigned to the forced labor tunneling detail. Infirmary files from the Dora camp record him as a patient in March 1945. After that, all trace of the 19-year-old Sinto is lost.

No one from the family of eight survived the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.

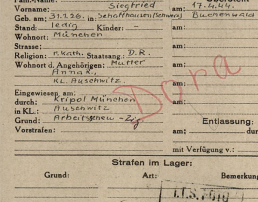

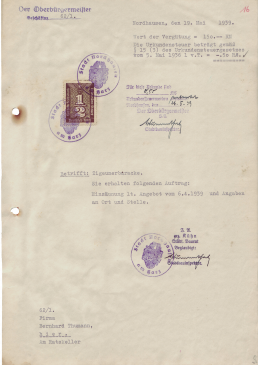

"Gypsy!" Police booking documents for Siegfried Reinhardt, 1942.

In most cases, local authorities and the police were actively involved in enforcing the bans, registering, and arresting Sinti and Roma. In 1942, Siegfried Reinhardt was arrested after skipping school several times. He was sentenced as a juvenile and sent to prison.

(Staatsarchiv München)

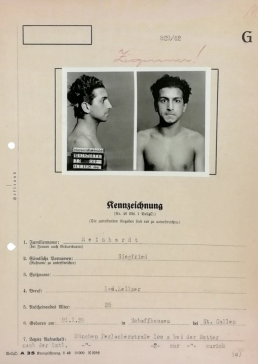

Grounds for imprisonment: "Workshy - Gypsy". Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Siegfried Reinhardt, 17 April 1944.

Siegfried Reinhardt remained in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp for only a few weeks. On 11 May 1944, the SS transferred him to the Harzungen subcamp, which became part of the independent Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in October 1944.

(Arolsen Archives)

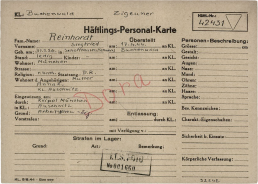

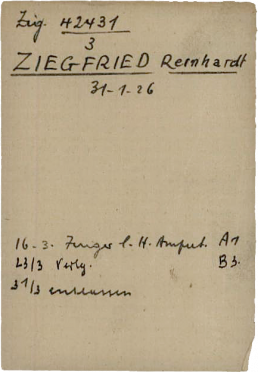

The last trace of Siegfried Reinhardt. Infirmary records from the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, March 1945.

In the file, the first name was incorrectly given as “Ziegfried.” On 16 March, the 19-year-old Siegfried Reinhardt had a finger on his left hand amputated, as can be seen from the document. He was released from the infirmary on 31 March. This is the last trace of the young man.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Excluded - Persecuted - Murdered

zugang

Children of Gemeinschaftsfremden (lit.: strangers to the community, those people who were not considered to be part of the Volksgemeinschaft) were marginalized and persecuted in the Nazi state. The National Socialists killed thousands of disabled boys and girls in euthanasia institutions. 1.5 million Jewish children and teenagers as well as an unknown number of young Sinti and Roma perished. They died in ghettos and camps as a result of hunger, violence and forced labor, were shot by death squads or suffocated in gas chambers.

Many children from the Soviet Union and Poland were brought to Germany, sometimes with their parents, for forced labor. The minimum age for foreign civilian workers was lowered further and further during the war. Tens of thousands of babies born to foreign forced laborers died in German custody.

Young people in Germany also had to reckon with persecution if they managed to evade the total grip of the state. Tens of thousands were sent to youth concentration camps after having been classified as members of oppositional youth groups or as “difficult.”

9-year-old Jewish schoolgirl Alice Rosenthal was forced to pose giving the Hitler salute for her school photo in Wiesbaden, 1934.

After the handover of power to the National Socialists in 1933, Jewish students were still allowed to attend public schools. After the pogroms in November 1938, they were forbidden to do so.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Humiliation of Jewish boys in front of their non-Jewish classmates in a Viennese school, 1938.

On the blackboard is written: “The Jew is our greatest enemy! – Beware of the Jew!” Beginning in 1938, Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend public schools in the German Reich, which included Austria.

(bpk)

Men of the SS lead away Jewish women and children after the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, May 16, 1943.

Presumably, almost none of the people taken away survived. It was long believed that the boy with his hands up was Zvi Nussbaum (1935-2012), a survivor of the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. Recent research suggests that may not be the case.

(bpk)

Arrival of a transport train at the ramp of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp, May 1944.

In 1944, the SS deported over 400,000 Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz, including many children. At the train ramp, SS doctors deemed most of the children unfit for work and sent them to the gas chambers. Some managed to pass themselves off as older to avoid certain immediate death. Several thousand children were transferred to other concentration camps, including Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora.

The photo is from an SS album.

(Yad Vashem)

Sinti and Roma in the Belzec labor camp, 1940.

In the spring of 1940, Sinti and Roma who had been deported from the German Reich were imprisoned in the camp in occupied Poland. They were transferred to another camp in May 1940. Later, the SS used the Bełżec site as an extermination camp for Jews.

(akg-images / Fototeca Gilardi)

Removal of children from the Antonius children’s home in Fulda, 21 July 1937.

43 children with disabilities were moved to a home in Treysa (Hesse). About half of them were later murdered in the Hadamar euthanasia institute. The other children survived thanks to a nurse’s rescue efforts.

(Antonius gGmbH, Fulda)

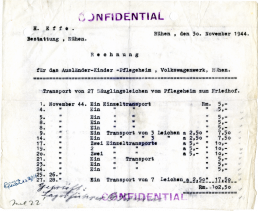

Invoice for the transport of infant corpses, 30 November 1944.

The children born to foreign forced laborers died in a “foreign children’s care institution” run by the Volkswagen plant. In total, several ten-thousands of foreign children starved to death in such homes between 1943 and 1945. This document from Rühen, near Wolfsberg, served as evidence in a British war crimes trial.

(The National Archives, London)

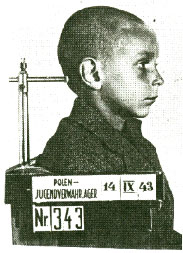

ID photo of an unknown boy in the Kinder KZ Litzmannstadt (Łódź), November 1943.

Between 1942 and 1945, more than 10,000 Polish children and teenagers up to the age of 16 were imprisoned in this camp in annexed western Poland. They had been arrested as relatives of resistance fighters, for neglect or theft of food. There were concentration camps for German children in Moringen and in Ravensbrück.

(Zukunft braucht Erinnerung)

"All ringleaders [...] are to be sent to a concentration camp. There the young people must first of all be beaten and then be drilled harshly and made to work [...] The stay in the concentration camp for these youth must be a longer one, 2-3 years. It must be clear that they will never be allowed to attend university again [...] Only if we take brutal action will we be able to avoid the dangerous spread of this Anglophile tendency at a time when Germany is fighting for its existence [...] I ask that this action be carried out in agreement with the Gauleiters and the Higher SS and police leaders.

Heil Hitler Ihr H. H."

Swing Kids to concentration camp: excerpt from Heinrich Himmler's letter, 26 January 1942.

The Swing Kids were an oppositional youth movement represented in many major German cities. Swing did not conform to the ideas of National Socialist ideology and was considered degenerate music. SS chief Heinrich Himmler called for a police crackdown and for the young people to be sent to concentration camps.

(Bundesarchiv)

Herrenkinder and Outcasts

Nothing found.

Integration into the Volksgemeinschaft

zugang

Nazi propaganda persuaded the children of the Volksgenossen that they were part of a superior Volksgemeinschaft (national community), giving them the feeling that they belonged to a Herrenrasse. Many young people readily accepted this idea.

National Socialism permeated the lives of children and young people, from the family to school to the Hitler-Jugend (Hitler Youth, abbreviated HJ), the youth organization in which almost all young Germans were involved. They were indoctrinated in the cult of the Führer, soldierly virtues, an ethno-nationalist worldview, and the cult of a healthy body.

School in the National Socialist era. Celebration in a Berlin elementary school on the anniversary of the founding of the German Reich in 1871, January 18, 1934.

In 1934 the Hitler salute became mandatory in German schools. National Socialist-influenced curricula and textbooks, especially in the subjects of history and biology, taught “racial studies.” As early as 1933, many teachers were already members of the Nazi Party and urged their students to join the Hitler Youth.

(Bundesarchiv)

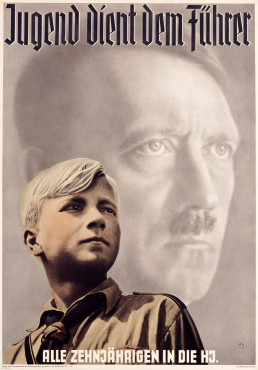

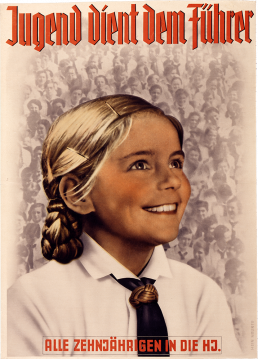

Indoctrination and the Cult of the Führer: advertising posters designed by the Press and Propaganda Office of the Reich Youth Leadership, c. 1939.

In 1936, the HJ was declared the sole state youth organization, and from 1939 onward membership was compulsory for German children and teenagers. But even before that, many had already joined voluntarily. The HJ was the Nazi Party’s youth organization and a state educational institution at the same time. It indoctrinated its members to absolute obedience and devotion to Hitler and the Volksgemeinschaft.

(Deutsches Historisches Museum)

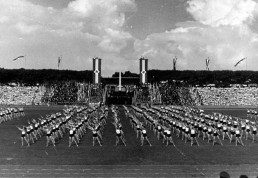

"Your body belongs to the nation": athletics pageant at the HJ sports festival in Essen, 1938.

Sports and military training played a central role in the education of children and young people. They were called upon to be constantly ready to perform. At the same time, sports was a means of fostering ideological indoctrination and preparation for war.

(NS-DOK Köln)

From the HJ to the SS: Waffen-SS propaganda postcard, Vienna, c. 1943.

The HJ was not only an organization for ideological indoctrination, it also provided military training. The quasi-military camps with marching drills and combat and weapons training were intended to prepare the boys in the HJ for their deployment in the war.

(Deutsches Historisches Museum)

SS-Rottenführer Hans Stark in Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1939.

Many concentration camp guards were not yet of age. Hans Stark, an enthusiastic Hitler Youth, joined the SS at a very early age. At only 16, he was assigned to the guard detail at Oranienburg Concentration Camp and was transferred to Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1938. There he looked after the horses of a cavalry platoon, but was also deployed for guard duty. Later, Hans Stark was among the SS troops deployed to the Dachau and Auschwitz Concentration Camps. In the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, the court found him guilty of having been complicit in murder and sentenced him to 10 years in juvenile detention. He died in 1991.

(Gedenkstätte Buchenwald)

SA for kids: HJ patrols. Hitler Youth propaganda photo.

The HJ patrols imitated the acts of persecution committed by the SA and SS. Children and young people who were seen as enemies could expect to be beaten up in the streets. During the war, the HJ patrols were also used as auxiliary police, to guard forced laborers, for example.

(NS-DOK Köln)

"Jugend führt Jugend": Jungvolk in Lippstadt, 1942.

Jugend führt Jugend (the young leading the young) was the propagandistic motto for the HJ program that trained its members to become HJ leaders. During World War II, the Wehrmacht (the German armed forces) drafted many older HJ members for military service. In many cases, inexperienced younger boys took over the leadership positions. Membership in the HJ, especially in the Jungvolk (the HJ division for boys 10-14), thus became less attractive than before.

(Lippstadt City Archive)

From the Hitler Youth to the Front: Young people armed with bazookas and carbines march to war in Lower Silesia, March 30, 1945.

In March 1945, compulsory military service was extended to those born in 1929. This meant that even 15-year-olds had to join the Wehrmacht, the Waffen-SS or the Volkssturm. Many of the boys sent to the front were untrained.

(Bildarchiv preußischer Kulturbesitz)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Exhibition, NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne: Jugend im Gleichschritt!? Die Hitlerjugend zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit.

museenkoeln.de.

Lebendiges Museum Online: Der Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM).

dhm.de.

Herrenkinder and Outcasts

Nothing found.

Franz Rosenbach

From Vienna via Auschwitz to Mittelbau-Dora

zugang

Franz Rosenbach was born on 29 September 1927 in Horaditz (Sudetenland). In February 1943, the Rosenbach family was arrested and imprisoned in Vienna. Deportation to the “Gypsy family camp” Auschwitz-Birkenau followed in 1944. The SS then transferred the 16-year-old Franz Rosenbach to the Mittelbau-Dora subcamp via the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in April 1944. There and in the Harzungen subcamp, he was forced to perform hard labor on construction sites.

In early April 1945, he survived a death march to Dessau. Franz Rosenbach made his way back to his hometown, but found none of his family. It was not until the early 1950s that he was reunited with his sisters Julie and Mizi in Nuremberg. The three were the only family members to survive.

Franz Rosenbach had to fight for decades to obtain German citizenship, which he did not receive until 1991. He was active for many years as deputy chairman for the Bavarian State Association of Sinti and Roma. Franz Rosenbach passed away in 2012 in Nuremberg at the age of 85.

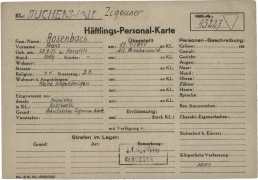

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Franz Rosenbach, 17 April 1944.

The document shows that Franz Rosenbach was arrested by the Vienna police because he was a Gypsy and subsequently deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. In April 1944, he was transferred as a forced laborer to Mittelbau-Dora via the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Arolsen Archives)

Franz Rosenbach recounts his experiences as a teenage forced laborer in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, and Harzungen in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 23 October 1998.

(Visual History Archive)

"If I had not been arrested, if I had learned my profession, today I would have a pension of maybe fifteen hundred euros or two thousand euros. I am on death’s doorstep, to put it plainly. Now I have to scrape together enough to pay for my burial expenses. It's really sad, but it's true."

Struggle for recognition and compensation. Franz Rosenbach in an interview with Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2012.

(Bayerischer Rundfunk)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Jakob Gerste

From Nordhausen to Auschwitz and back again

zugang

Jakob Gerste was born near Gotha on 6 May 1926. The family moved to Nordhausen in the 1930s. In March 1943, he and several siblings were arrested and deported to the “Gypsy family camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where his brothers Rudolf and Heinrich were murdered.

In Auschwitz, Jakob Gerste was assigned to the forced labor bricklaying detail. In April 1944, the SS transferred him via Buchenwald to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, within sight of his hometown Nordhausen. He was assigned to the forced labor construction site detail. He survived and was liberated in Bergen-Belsen in April 1945. He spent the rest of his life in Holzminden (Lower Saxony). Of his family, only he and his sister Emma survived the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.

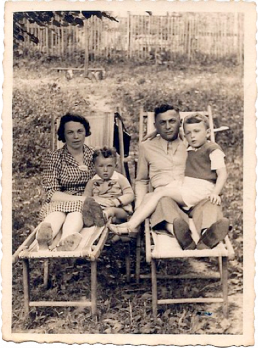

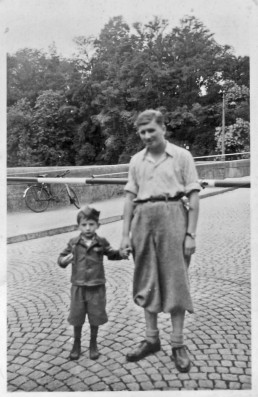

The Gerste family in Nordhausen, around 1938.

From left to right: Anna, Rudolf, Jakob (standing), Hermann, mother Blondine with son Heinrich, Emma and Erwin. At the time this picture was taken, the father Robert Wagner had already been sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg)

Order from the building authority of the city of Nordhausen to the Bernhard Thumann company to fence in the "Gypsy barracks" at Holungsbügel, 19 May 1939.

In October 1939, a few months after this order for fencing was placed, the Sinti and Roma were forbidden to leave their places of residence. The Gerste family was forced to move their caravan to the fenced-in area next to the “Gypsy barracks” on the outskirts of town.

(Kreisarchiv Nordhausen)

"The Nordhausen Gestapo imprisoned us in March 1943. It was early in the morning. We had to leave everything behind, we could only take what we were wearing with us."

Interview with Jakob Gerste,

17 September 2000.

(Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg)

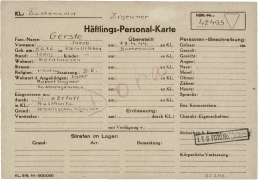

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Jakob Gerste, 17 April 1944.

On 17 April 1944, the SS transferred Jakob Gerste from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald. The place of residence of his father is given as Neuengamme Concentration Camp. The writing in red letters ‘Dora’ refers to the transport to the Mittelbau-Dora camp a few days later. On the card, there is written an incorrect date of birth.

(Arolsen Archives)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Shraga Milstein (Feliks Milsztajn)

From Poland to Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen

zugang

Feliks Milsztajn was born in 1933 in the Polish town of Piotrków Trybunalski. In October 1939, the German occupiers forced the Jewish family to move into a ghetto. His mother was deported to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in 1944; the SS sent him, his brother, and his father to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in late 1944, where his father died.

In January 1945, the SS transferred Feliks Milsztajn and other children to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. The camp was liberated on 15 April 1945. Later, he learned that his mother had also been deported to Bergen-Belsen. She died shortly after the liberation, without the two of them having seen each other again.

In May 1945, the 12-year-old was able to have his 9-year-old brother, who had been left behind in Buchenwald, brought to Bergen-Belsen. A short time later, the two were sent to a children’s home in Sweden before leaving for Israel in 1948. There, Feliks changed his name to Shraga Milstein and became a teacher and the director of the Massuah Institute for Holocaust Studies. Since 2019, he has been the chair of the advisory board of the Lower Saxony Memorials Foundation.

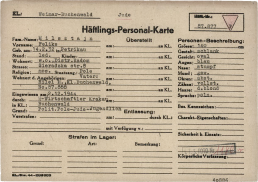

Buchenwald Concentration Camp prisoner registration file for Feliks Milsztajn (today Shraga Milstein), 2 December 1944.

One month later, the SS transferred Feliks to Bergen-Belsen. On the form, his date of birth is given as 1932 rather than 1933. His father had told the SS that his son was a year older in order to protect him.

(Arolsen Archives)

“In Nov. 1944, we were shipped in a cattle wagon to Germany – my father, brother, and myself to Buchenwald, my mother to Ravensbrück. When we parted at the train station was the last time, I saw her. A few days after our arrival in Buchenwald, my father came back to our barracks in the evening with a stern look in his eyes. He took my brother and me aside and said: "we have to part and we will not see each other anymore. Take care of your younger brother, remember your names and the fact that you have family in Palestine." He gave us a hug and we went to sleep. I later learned that the next day he was killed at the age of 43. All my efforts, during the years, to find out what happened and how he knew his fate, were in vain. A few weeks later, I was transferred with a group of friends my age to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp.”

From Shraga Milstein's Holocaust Remembrance Day speech at United Nations Headquarters in New York, 27 January 2020.

(United Nations)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Joseph Schleifstein

(Szlajfaztajn)

A three-year-old in Buchenwald

zugang

Joseph was born to Israel and Esther Szlajfaztajn on 7 March 1941 in Sandomierz, Poland. At the end of 1942, the German occupiers established a ghetto for Jews in the city, and the family remained there until its dissolution in January 1943. In January 1945, the entire family was deported to the German Reich. Esther was sent to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, and Israel and three-year-old Joseph arrived at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 20 January 1945. With the help of his father and other prisoners, he survived until liberation.

In 1946, Joseph and his father reunited with his mother Esther in Dachau, which was now a DP camp. In 1947, the family emigrated to the USA and built a new life for themselves in New York.

The story of Joseph Schleifstein, who is said to have been smuggled into the Buchenwald camp in a sack, served as the basis for Roberto Benigni’s internationally acclaimed Italian tragicomedy La vita è bella in 1997.

Joseph Schleifstein in a group of children and adolescents from the liberated Buchenwald Concentration Camp in the Rheinfelden quarantine camp in Switzerland, June 1945.

Joseph and other juvenile Buchenwald survivors were taken to Switzerland for recuperation on a Kindertransport (children’s transport). He later rejoined his father.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Deterrence through forced labor: Disciplinary work prisoners

zugang

From 1941 to 1944, a Gestapo labor re-education camp existed at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Labor re-education camps (Arbeitserziehungslager, AEL) served as punishment for civilian workers, especially foreign laborers, who were accused of refusing to work. The temporary “disciplinary labor” was intended to instill a work ethic.

Between April 1941 and March 1944, almost 2,000 boys and men were sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp as labor re-education prisoners. The SS released most of them after three to eight weeks. Some, however, did not survive the hard forced labor.

Beginning in November 1942, nearly all prisoners in the Buchenwald AEL were children and adolescents from the Soviet Union sent there by the Gestapo. The juvenile labor re-education prisoners were housed together in Block 8, later known as the Children’s Block. From mid-1943 onwards, no AEL prisoners were released. Almost all of them remained as concentration camp prisoners at Buchenwald.

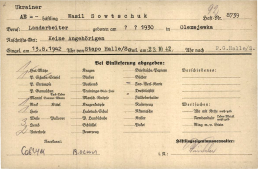

Personal effects file for Wasil Sawtschuk, 13 August 1942.

On 13 August 1942, the Halle State Police delivered 12-year-old Wasil Sawtschuk (Sowtschuk in some documents) to the Buchenwald labor re-education camp. Ten weeks later he was released and transferred back to prison in Halle. Wasil Sawtschuk was one of the youngest labor re-education prisoners at Buchenwald.

(Arolsen Archives)

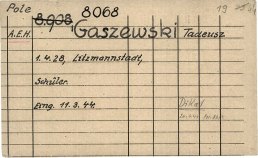

From the Buchenwald Concentration Camp file on Tadeusz Gaszewski, 11 March 1944.

The Gestapo sent Tadeusz Gaszewski, a schoolboy from Litzmannstadt (Łódź), to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 11 March 1944. He was the last person to be admitted as a labor re-education prisoner.

(Arolsen Archives)

From the Buchenwald Concentration Camp file on Tadeus Gaszweski, 11 March 1944.

Tadeusz Gaszewski was sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp as a labor re-education prisoner. However, the SS registered him as a prisoner in the category “political Pole – juvenile.” It is not known if Tadeusz Gaszewski survived.

(Arolsen Archives)

Forced labor in the armaments factory. Buchenwald railroad siding at the Gustloff Plant II, 1943.

In 1942, construction of the Gustloff Plant II began at Buchenwald. After its completion, the SS’s interest in labor re-education prisoners declined, since the plant used primarily concentration camp inmates for its workforce. In 1943, the Gestapo established a central AEL for Thuringia at Röhmhild in the Thuringian Forest. Almost all prisoners sent to the Buchenwald AEL were juveniles. They had to work in the particularly difficult excavation and construction details on the premises of the Gustloff Plant II or in railroad construction. Many of them died.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"In the Construction Detail I we had 250 young people, citizens of the Soviet Union, Poland and Jews. We were looking for ways to save the young people from perishing. [...] About 150 teenagers had to carry bricks from the storage area, where the bricks were stored, about 2000 m to the Gustloff Plant II construction sites (hall construction).

The first day they carried 2 bricks on their shoulders, in their hands or arms. The second day, SS-Scharführer Schmidt’s overseers at the storage area forced them to carry 4 bricks. The SS Scharführer started yelling like rabid dogs: Carry the bricks faster, pick them up faster, run faster! And he ran alongside them for a few hundred meters. They beat the boys, making them fall down, dropping the stones in fear. The result was that broken bricks were brought to the construction site."

Report by Ernst Plaschke on the AEL prisoners as forced laborers in Buchenwald, April 1979.

Unskilled juvenile AEL prisoners had to perform particularly hard forced labor. Ernst Plaschke was Kapo of Construction Detail I in Buchenwald. After his liberation, the former political prisoner described the conditions under which the young people had to haul bricks to the Gustloff Plant II construction site.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Lebendiges Museum Online: Arbeitserziehungslager im Deutschen Reich. Deutsches Historisches Museum

dhm.de.

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.