Liberated on death marches

Month: March 2021

As Allied troops approached in early 1945, the SS began to clear the first subcamps of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, evacuating the prisoners to the main camp or to other camps. In early April, US troops advanced into Thuringia and the SS began evacuating the main camps at Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora. Some prisoners were evacuated by rail, but the SS also drove many of the exhausted prisoners on forced marches. Thousands of men, women and children died in the railway wagons, and even more on the death marches.

Some prisoners managed to escape during the evacuation transports. They hid and were liberated by US and Soviet troops.

Death march, escape, hiding. Magda Brown talks about her liberation in March 1945 in an interview, 2014.

Magda Brown (née Perlstein) was born in Miskolc (Hungary) on 11 June 1927. At the age of 17 she was deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, then later that same year she was transferred to the Münchmühle subcamp as a forced laborer in an explosives factory in Allendorf, Hesse. The SS cleared the camp in March 1945, and the prisoners were marched to Buchenwald. During the march, the young woman managed to escape. She and 20 other women hid in a barn, where they were liberated by US soldiers.

(private property/magdabrown.com)

Photo of the barn where Magda Brown and other prisoners from the Buchenwald subcamp Münchmühle hid in 1945, after 1945.

After a day and a half in hiding, Magda Brown and the other women were discovered and liberated by two soldiers from the US Army’s 6th Armored Division.

(private property/magdabrown.com)

"No one yet understands that we have been left behind. There is really no one guarding us anymore! Halina and some girls decided to go to the village [...]. In the clearing lie the sick and weak women in blue-grey striped prisoners' clothes, the color of which clashes with this spring-like fresh green.

The girls return [...]. They are happy, smiling, screaming, crying with joy. THE END OF THE WAR!!! These most glorious words fall unexpectedly and gives strength.

The women run in different directions. They are free, free at last. I don't believe it yet. How did this happen? 'The Soviet army is in the village, we talked to the soldiers,' says a female comrade."

Maria Brzęcka recalls her liberation by Soviet soldiers on 5 May 1945, circa 1990.

Maria Brzęcka and her sister Halina were driven on a death march from the Meuselwitz subcamp toward the Czech Republic in mid-April 1945. Maria, who was completely exhausted, turned 15 while on the march. Shortly before reaching Prague, the SS guards ran off and the prisoners were free.

(Als Mädchen im KZ Meuselwitz – Erinnerungen von Maria Brzęcka-Kosk, Dresden 2016)

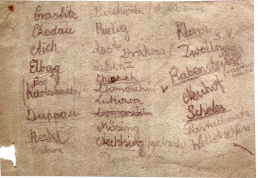

Notes written by Maria Brzęcka while on the death march, April/May 1945.

Maria Brzęcka noted the stations of the death march from Meuselwitz towards Prague.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

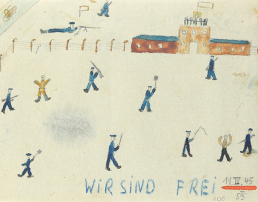

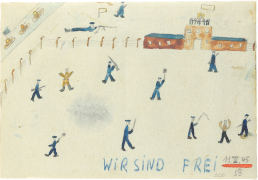

"Death March," watercolor painting by Polish-Jewish artist Walter Spitzer, 1945.

Walter Spitzer was born in Cieszyn on 14 June 1927. Deported from Poland, he arrived in Buchenwald on 10 February 1945 after a death march from Auschwitz via the Groß-Rosen Concentration Camp. The SS sent the 17-year-old on another death march on 7 April 1945. He managed to escape, and US soldiers liberated him near Jena.

(Ghetto Fighters’ House – Beit Lochamei HaGeta’ot)

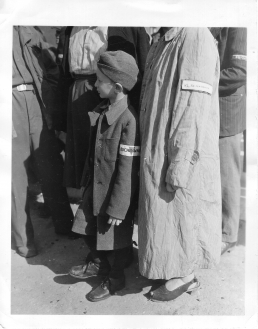

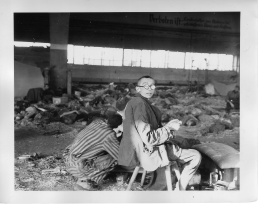

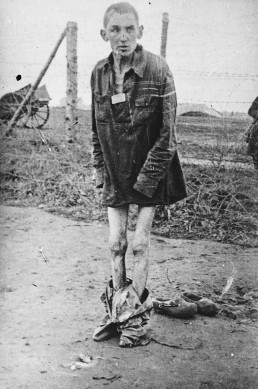

US medical personnel treat an 18-year-old Soviet survivor of the Gardelegen massacre, April 1945.

SS members, Luftwaffe soldiers, and members of the Volkssturm and Reich Labor Service set a barn on fire on the outskirts of Gardelegen, murdering more than 1,000 concentration camp prisoners during the night of 13-14 April 1945. They were stranded in Gardelegen while on death marches from the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp and camps in Hanover. Among those murdered were about 100 adolescents ; three sixteen-year-olds are known by name. Only a few prisoners survived the massacre.

(NARA)

Liberations

Nothing found.

PLAY

CONTACTS

FANTASY

HOPE

In order to escape the grim reality of life in the camp, which was characterized by violence and the fear of death, many children and young people tried to create a world using their fantasy or by playing games. Some also created fantasy worlds through drawing.

For the children and young people who had been deported to the concentration camp alone, contact with fellow prisoners was essential to maintain the will to survive. The young prisoners gave each other hope and comfort. Contacts with adult prisoner functionaries with influence were also essential for survival.

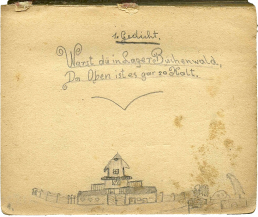

"Warst du im Lager Buchenwald, da oben ist es gar so kalt" (If you were in the Buchenwald camp, it's so cold up there). Poem and drawing by Johann Stojka, 26 February 1945.

The 15-year-old Rom was deported from Auschwitz to Buchenwald with his brother in the summer of 1944. He recorded his experiences with verses and drawings in a notebook. His poem ends on a hopeful note with the words, “We’ll get out after all.” The two brothers were the only members of their family to survive.

(Kazerne Dossin, Mechelen)

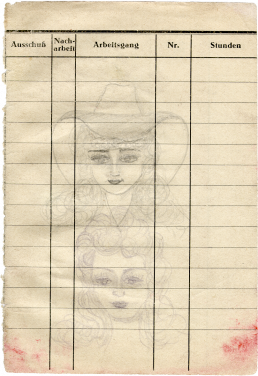

Drawing by Maria Brzęcka from the Meuselwitz subcamp, 1944/45.

To escape the reality of the Meuselwitz women’s camp, Maria Brzęcka, then 14 years old, drew. Using a small pencil and old inspection slips from the factory where she had to do forced labor, Maria created her “own dream world.” She drew scenes from life before the war, which she had older fellow prisoners describe to her. She also made drawings of extravagant female figures, many of which have been preserved.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

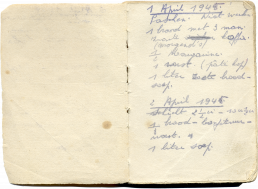

Diary of Leopold Claessens, 1-2 April 1945.

Secretly keeping diaries or notes was also a strategy of self-preservation and survival. The Belgian teenager Leopold Claessens was deported to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp as a political prisoner at the age of 19. In April 1945, he survived an evacuation transport to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. He started the diary in Bergen-Belsen, writing in retrospect, and recorded what he was given to eat

(private property)

Flowers for Bread. Franz Rosenbach in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 23 October 1998.

The Sinto Franz Rosenbach arrived at Mittelbau-Dora when he was 17. In the camp, hunger was a constant companion. To supplement his meager bread ration, he began picking flowers in his free time and exchanging them with the block elder for bread. Contact with the privileged prisoner functionaries could be essential for survival.

(Visual History Archive)

"With Daddy at the Zoo." Camp commander Karl Otto Koch with his son Artwin at the Buchenwald zoo, October 1939.

In 1938, the SS built a zoo on the Ettersberg. It served as a recreational facility for the SS and their families. While opportunities to play were limited for the children suffering in the camp, the children of the SS personnel amused themselves at the zoo just outside the camp fence.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Humor was an essential part of our mental resistance. And this mental resistance was, in short, a necessity for having the will to live. I tell you this as an ex-prisoner. No matter how rarely it occurred, how sporadically or how spontaneously, it was of great importance. Of very great importance!"

Humor as a means of survival. Felicija Karay in an interview, c. 2000.

From July 1944 to April 1945, 17-year-old Felicija Schächter (married name Karay) worked as a forced laborer for HASAG Leipzig. In an interview with psychologist Chaya Ostrower, she described humor as a means of mental resistance.

(Chaya Ostrower: It Kept Us Alive. Humor in the Holocaust, Wiesbaden 2018).

"Hasag is our father,

The best father there is!

He promises us

Long years of happiness,

Chorus:

The command’s for

Law and order, no more!

That we calm our nerves

Before we become

A can of preserves […]

HASAG Hymn. Prisoners’ humorous song, before 1945.

The women and girls who worked as forced laborers in the HASAG Leipzig subcamp wrote a humorous anthem, which they often sang together. It satirized the conditions in the camp.

Felicija Karay: Hasag Leipzig Slave Labour Camp for Women: The Struggle for Survival, Told by the Women and Their Poetry, Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd, 2003).

Scene from the fairy tale Snow White. Plaster fresco by French prisoner Georges Sanchidrian in the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp, 1944.

Georges Sanchidrian made colored murals on the plastered walls in Block 4 of the Mittelbau-Dora subcamp. Some frescoes with fairy tale scenes survived. Both adults and juvenile prisoners were housed in the block. Sanchidrian (born 1905) died on a death march in April 1945.

(German Historical Museum)

Realms of Experience

Nothing found.

Children's transports after the liberation

Month: March 2021

The parents and other relatives of the approximately 900 underage survivors of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp had almost all been murdered. Other orphans were brought to Buchenwald from other camps after liberation. For most of them, returning to their homes was unthinkable. The Allies and international aid organizations cooperated in placing them orphanages and care homes. The organization Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE) played a special role. Switzerland took in 374 children and young people from Buchenwald, France took in 480, and England took in 250. Many of them wanted to emigrate to Palestine.

Most of the surviving children and adolescents from the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp were liberated in Bergen-Belsen. From there, transports were organized to many countries, including Sweden.

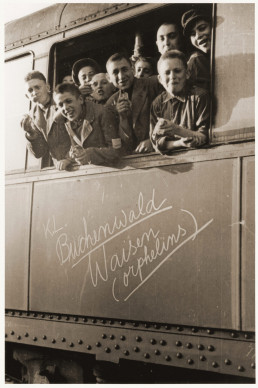

"Where are our parents?" Children and teenagers liberated from Buchenwald at Weimar's main station on a train to Écouis (France), 1 June 1945.

Jozef Dziubak, a 17-year-old Jewish boy deported from Poland, writes in a mixture of German and Yiddish on one of the train cars, “Where are our parents? You (Nazi) murderers.” The train carried more than 400 liberated children and young people to France.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Orphans.” Liberated teenagers on their way to a children's home in Écouis, June 1945.

Due to the acute clothing shortage in the liberated camp, the US liberators had dressed some of the children and young people in Hitler Youth uniforms. In France, their train was attacked because they were mistaken for Nazis. The inscriptions on the wagons “K.L. Buchenwald” and “Orphans” served to protect the passengers. At one stop, the boys crowded to the window. Jacques Rybsztajn (second from left) and Arthur Fogel (bottom right) can be seen in this photo.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Jewish teenagers with a Star of David flag before their departure from the liberated Buchenwald camp, 5 June 1945.

The two girls Yetti Halpern Beigel (left) and Martha Weber (right) were prisoners at the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. After liberation, they were sent to the Buchenwald DP camp for medical treatment. Together with an unnamed youth from Latvia (center), they were photographed shortly after their departure for France. The girls planned to continue their journey to Palestine.

(Photo: James E. Myers, Buchenwald Memorial)

Arrival: At the Écouis train station, the children and teenagers are welcomed by the authorities, 5 June 1945.

After the train ride, they were welcomed by staff members of the aid organization for Jewish children, OSE. Most of the children and young people remained in France until 1947/48.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

A Swiss newsreel reports on the arrival of the "Buchenwald Children," 29 June 1945.

Rabbi Herschel Schacter accompanied the children and young people on their trip from Buchenwald to Switzerland. Among the children seen in the reel is the four-year-old Joseph Schleifstein. When the “Buchenwald children” arrived in Switzerland, the authorities and the press were surprised at the ages of some of them. The humanitarian aid operation was to have brought only children and adolescents up to 18 years of age to Switzerland, but there were also many homeless young adults who needed a perspective for the future.

(Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv)

"Buchenwald children" in Geneva, 1945/46.

The young people in the OSE homes were not only nursed back to health, they also learned trades in order to be able to build new lives for themselves. Pictured in this group photo in front of the Hôme de la Forêt in Geneva are Gert Silberbard, Gilles Segal and Norbert Bikales.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

New accommodations in Switzerland: Hôme de la Forêt in Geneva, 1945/46

The children and young people from Buchenwald who were taken in by Switzerland were housed in various orphanages and care homes. In Geneva, the Hôme de la Forêt was made available, and the relief organization OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) provided care.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

"It was a great effort to bring us back to life." Account by Shraga Milstein on the transport to Sweden, February 2021.

In the fall of 1944 when he was 11 years old, Shraga Milstein was deported from a forced labor camp in Poland to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, along with his younger brother and father. His father died there, and the brothers were separated in January 1945 when Shraga was transferred to Bergen-Belsen. Both brothers survived and were taken to Sweden in the summer of 1945 with a group of other children who had survived the camps.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

After liberation

Nothing found.

Erich Davidsohn

As a young "special operation Jew" in Buchenwald

Month: March 2021

Erich Davidsohn was born in Hanover in 1922. He was the only child of Richard and Elfriede Davidsohn. He grew up in Salzhemmendorf, a village near Hamelin, in Lower Saxony. The Davidsohns looked after the small synagogue. They and one other family were the only Jews in the village. In 1935, Erich began an apprenticeship in his father’s butcher shop.

In the early morning hours of 10 November 1938, SA men ransacked the local synagogue and destroyed the interior. Erich Davidsohn and his father were taken into Schutzhaft (lit. “protective custody,” but actually preventive detention) and sent from the Hamelin penitentiary to Buchenwald. There, their heads were shaved, and they faced beatings and hunger on a daily basis.

In early December 1938, the SS released the 16-year-old Erich Davidsohn from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, presumably because of his age. His father was released a few days later. On 6 February 1939, Erich was able to emigrate to England. His father, mother, and cousin emigrated to Argentina.

Erich (left) with his mother Elfriede, his father Robert Davidsohn, and his cousin Juliane Guttmann in Hanover, 1939.

As early as 1935, Robert Davidsohn began preparations for his family’s emigration to South America. But it was not until 16 June 1939, a few months after his return from Buchenwald, that he succeeded in getting himself, his wife, and his niece Juliane to Buenos Aires. Erich Davidsohn left for England in February 1939. His mother had registered him for a Kindertransport (children’s transport) while he was being held at Buchenwald. He never saw his parents again.

(private property/Mel Davidsohn)

"After the first week names were called and releases started. On the morning of 6 December my name was called. You had to rush to the gate or miss being released. A quick farewell with my father and I was away. We had to stand in line near the offices all day and not move. No food was given and, worst of all, we couldn’t go to the toilet. We were then given money for the rail fare and were bussed to the station. Several of us got on the train direct to Hanover and we arrived in the middle of the night. The other people on the train kept well away from us, possibly because they knew who we were and where we had been. And, of course, we were very dirty and literally stank."

Erich Davidsohn on his release from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, after 1939.

(https://pogrome1938-niedersachsen.de/salzhemmendorf/)

Stolperstein in Salzhemmendorf for Erich Davidsohn, 7 March 2020.

Since 1995, Cologne based artist Gunter Demnig has been commemorating the victims of the Nazi regime with his project Stolpersteine – Stumbling Stones. All over Germany, the artist lays small brass memorial stones in sidewalks in front of buildings where individuals who were persecuted and murdered by the Nazi regime lived or worked.

(CC)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Lower Saxony Memorial Foundation, November Pogrom 1938 in Lower Saxony:

stiftung-ng.de/…/-pogrom-1938-in-lower-saxony/

Novemberpogrome 1938 in Niedersachsen, Salzhemmendorf:

pogrome1938-niedersachsen.de.

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.

Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich 1938

Month: March 2021

In 1938, the number of prisoners in the concentration camps doubled. As part of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich, two waves of arrests of purported “anti-social elements”), the police sent over 10,000 men and several hundred women to the camps – most of them were adults, but some were teenagers. About 4,000 men were sent to Buchenwald, including about 1,200 Jews. For a brief time, the majority of prisoners in the camp were those with a black triangle identification badge, which marked prisoners as “anti-social”.

All those who were not a part of the “national community”, such as the unemployed, beggars, vagrants and those persecuted as gypsies, were considered “anti-social” or “alien to the community.” The police worked closely with the labor and welfare offices during the waves of arrests.

It was not until 2020 that the Bundestag (German parliament) recognized those persecuted as anti-social as victims of the Nazi regime.

"They called them work-shy. We are forbidden to talk to them. Mostly they are people with physical or mental disabilities who are taught to work here in the camp. They get the black mark. [...] Young people with spindly legs are supposed to learn how to work here under the supervision of the SS, who are fed to the hilt. [...] The accommodation of the "work-shy" is nothing more than a disgrace itself. From one day to the next they built a large barracks below the other barracks, with next to nothing in it. That’s how they live and they die en masse."

Report by the political prisoner Moritz Zahnwetzer on the arrival at Buchenwald of those arrested in the 1938 Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich, 1946.

(Moritz Zahnwetzer: KZ Buchenwald. Erlebnisbericht Kassel 1946)

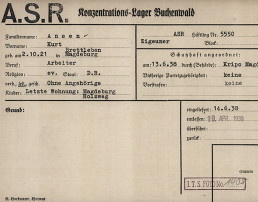

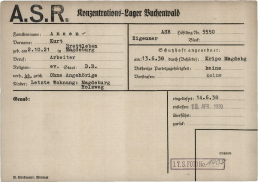

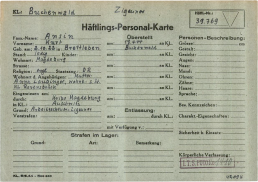

Kurt Ansin’s prisoner ID, 1938.

Kurt Ansin was arrested at age 16 for being a gypsy and sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in June 1938. His file was stamped by the SS with the abbreviation “A.S.R.” (Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich). Kurt Ansin had to wear the black triangle designating him as anti-social on his prison uniform.

(Arolsen Archives)

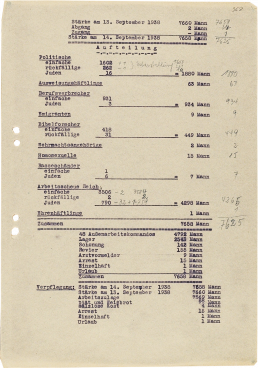

"Guidelines for the Registration of those Unfit for the Community," Office of Racial Policy Styria, December 1942.

The Volksgemeinschaft ideology was not only racist, but also included the idea of achievement. People without work were considered unworthy and seen as ballast, and were therefore to be disciplined through forced labor. The idea of “unfit for the community” was interpreted very broadly.

(Landesarchiv Steiermark)

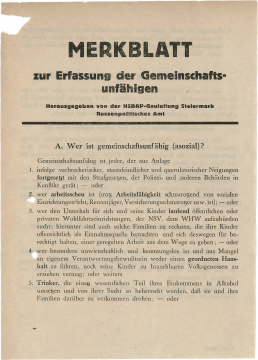

"Crime Prevention Measures.” Decree from Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo, Security Police) and head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service) to police commissioners, 1 June 1938.

The incarceration of those arrested on grounds of being anti-social in concentration camps took place in two waves in 1938. The decree of 1 June 1938 propelled the second wave of arrests later that month.

(StA Marburg)

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.

The Camp

Month: March 2021

In July 1937, the first prisoners arrived at Ettersberg near Weimar. The SS forced them to build a concentration camp for 8,000 male prisoners. Both political opponents of the regime and those persecuted for racial and social reasons were to be interned there.

By the end of the war, the Buchenwald Concentration Camp had developed into the center of a complex camp system with a total of 139 subcamps, where prisoners served as forced laborers for the armaments industry. In total, around 280,000 people were imprisoned at Buchenwald, and more than 56,000 died.

Not only men, but also women, teenagers and children were imprisoned in Buchenwald and its satellite camps. Children were in particular danger. Because they were unable to work, they had hardly any chance of survival. To protect them from forced labor and deportation to certain death, political prisoners built shelters for children and adolescents in selected barracks.

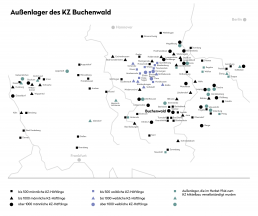

Beyond the main camp: A dense network of subcamps.

Most of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp’s subcamps camps were established after 1942, the turning point of the war after the Battle of Stalingrad. Prisoners were used for cleanup work in the cities and for forced labor in the armaments industry.

(Studio IT’S ABOUT)

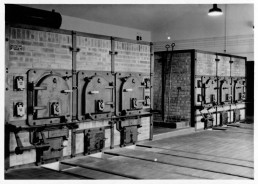

Interior of the crematorium at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1943.

Before 1940, the deaths of prisoners from the Buchenwald Concentration Camp were registered and their bodies cremated at the municipal crematorium in Weimar. In order to conceal the increasing number of prisoners murdered at the camp, a separate crematorium was built on camp premises in the summer of 1940. The incinerators were made by the Erfurt company Topf & Sons, which also manufactured the incinerators for the Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

The photo is from an album that camp commandant Hermann Pister had created for representational purposes.

(Musée de la Résistance et de la Deportation)

Children of SS members pose in front of a toy cannon in the Führersiedlung at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1943.

The SS barracks and housing estates were located only a few meters from the camp on the Ettersberg. SS officers and their families lived in the Führersiedlung.

(Photo: Georges Angéli, Buchenwald Memorial)

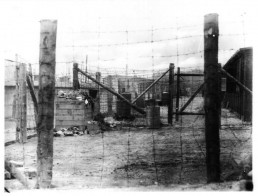

Camp road and barracks in the Little Camp, after liberation, April/May 1945.

In the Little Camp, which was established in 1942 as a quarantine zone for prisoners arriving on the mass transports, conditions were catastrophic. From 1944 onwards it was permanently overcrowded; starvation and death were ever-present. Political prisoners managed to establish a place of refuge for children, most of them Jewish, in Block 66 of the Little Camp.

(Photo: Alfred Stüber, private property)

Jurek Kestenberg on his memories of Buchenwald in an interview with David P. Boder, Fontenay-aux-Roses (France), 31 July 1946.

Jurek Kestenberg was born in Poland in 1929. He and his parents were deported from the Warsaw Ghetto to Majdanek in 1943. In August 1944 he was sent to Buchenwald. He survived thanks to the help of fellow prisoners. After liberation, he traveled to France on a children’s transport in June 1945, where Boder interviewed him in Yiddish.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation, Historical Overview of the History of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, 1937-1945: buchenwald.de/en

Förderverein Buchenwald e.V.: „Buchenwald war überall – die Errichtung eines Netzwerkes der Außenlager“:

aussenlager.buchenwald.de.

“Gedenksteine Buchenwaldbahn. Ein Projekt der Initiative “Gedenkweg Buchenwaldbahn”:

gedenksteine-buchenwaldbahn.de.

Children in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Nothing found.

Buchenwald DP camp and Kibbutz

Month: March 2021

In the course of World War II, the Germans deported several million people to the German Reich. After liberation, the Allies registered them as Displaced Persons (DP) and organized their return to their countries of origin. DPs were not only concentration camp survivors, but also liberated civilian forced laborers, especially from Eastern Europe.

After the war, DP camps were set up in all German occupation zones, including at the liberated Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora camps. For many survivors, however, repatriation was not possible, especially for the Jewish orphans. Some of them founded the Kibbutz Buchenwald in order to prepare for their joint departure to Palestine and their future life in a Jewish community.

In early July 1945, Thuringia became part of the Soviet occupation zone. The Buchenwald DP camp was transformed into a “repatriation camp” under Soviet management and was disbanded in October 1945.

Allied banner at the main entrance of the Displaced Persons Center II in Buchenwald, April/May 1945.

After the liberation of the concentration camps, about 2,000 DP camps were established in Germany, Austria and Italy. The former Buchenwald Concentration Camp served as a reception and transit camp for former prisoners and forced laborers.

(Photo: Alfred Stüber, Buchenwald Memorial)

Joseph Schleifstein on a UNRRA truck at the Buchenwald DP camp, after 11 April 1945.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was responsible for the DP camps and organized the repatriation of the survivors to their countries of origin. The photo of the 4-year-old concentration camp survivor Joseph Schleifstein was taken at the liberated Buchenwald camp.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

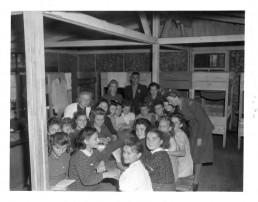

A UNRRA staff member with orphans in the Dora DP camp, 29 June 29 1945.

A DP camp was also established in the liberated Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp. In May 1945, more than 20,000 liberated forced laborers and several hundred concentration camp survivors were housed here. UNRRA staff took care of orphans whose parents had died as forced laborers or concentration camp prisoners.

(Photo: Edward Vetrone, Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp Memorial)

Commemoration ceremony organized by Jewish DPs in the liberated Buchenwald camp, June 1945.

In the Buchenwald DP camp, survivors organized many cultural events shortly after liberation. These included religious festivals and services as well as commemoration of the dead. At the center is Joseph Schleifstein wearing his striped prisoner suit.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

"Of the survivors, a considerable number will endeavor to find a new home in Palestine. After the unspeakable suffering that these people have endured, it is the duty of the Zionist public to fight to ensure that these Zionists are offered the opportunity to immigrate to Eretz Israel as soon as possible. [...] Obtain special certificates for children and young people who are still [...] in the camps and most of whom are orphans. Create for these children the possibility of a hakhshara in Western Europe, otherwise they will become dependent on public welfare when they return to their former homeland. Save the rest of the Jewish youth in Central Europe!"

"Obtain special certificates for children and youth". Appeal of the Jewish Relief Committee, 22 April 1945.

Palestine was one of the main destinations for emigration of Jewish survivors. Until the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, the country was still under British Mandate, and entry was strictly regulated. The Zionist movement had established so called hachsharas as early as the 1920s to offer agricultural training in preparation for emigration.

(Ghetto Fighters’ House – Beit Lochamei HaGeta’ot )

Young members of Kibbutz Buchenwald sing partisan songs outdoors at Gehringshof, summer 1946.

The Kibbutz Buchenwald at Gehringshof existed from June 1945 to October 1948. During the preparations for departure to Palestine, a variety of cultural events took place there. In 1948, the Kibbutz moved to Israel and in 1950 it changed its name to Netzer Sereni.

(Photo: David Marcus, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Kibbutz Buchenwald. Group photo in front of the agricultural training center in Gehringshof, 1945.

On 3 June 1945, Jewish survivors founded the Kibbutz Buchenwald in Eggendorf near Weimar. Before Thuringia became part of the Soviet occupation zone in July 1945, the approximately 50 members, most of them adolescents, moved to Gehringshof near Fulda. Kibbutz Buchenwald (written in Hebrew letters on the wall of the house) served as preparation for emigration to Palestine.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

FURTHER INFORMATION:

Juliane Wetzel: Displaced Persons (DPs), in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns,

historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de.

After liberation

Nothing found.

Liberated in Buchenwald and Mittelbau Dora

Month: March 2021

In the fall of 1944, the SS began to clear the camps in the east. Tens of thousands of prisoners arrived at Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora on evacuation transports from Auschwitz and elsewhere. Among them were many children and adolescents.

In early April 1945, the US Army reached Thuringia. The SS began to clear out Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora. They sent almost 70,000 people on rail transports or forced marches to Dachau, Theresienstadt or Bergen-Belsen. Many did not survive.

On 11 April, American tanks reached the Ettersberg, forcing the SS to flee. Political prisoners took control of the camp. Buchenwald was thus liberated both from the outside and the inside. Among those liberated were nearly 900 children and young people.

In the southern Harz, the SS succeeded in completely clearing almost all of the Mittelbau concentration camps. Only in the Dora and Boelcke garrison camps were a few hundred sick and dying people left behind. They were liberated by the US Army on 11 April.

"What will happen then? Will we be evacuated? But where to? In the south they are approaching Halle.... To the north, another attacking force is approaching Hanover. Towards the east? Surely not far, because 300 kilometers from us is the Russian front. We are very afraid of the evacuation, because we know how those from Auschwitz and Groß-Rosen suffered during the transport."

Diary entry by Emile Delaunois, 1 April 1945.

The closer liberation came, the more uncertain the situation became for the prisoners. They feared death marches and massacres by the SS. Emile Delaunois (born Louis Lelong in 1910), was a clerk in the Woffleben subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp. He died shortly after liberation in the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp.

(Mittelbau-Dora Memorial)

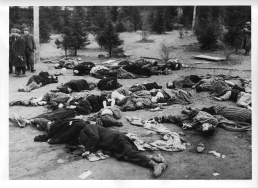

Murdered prisoners in the north camp of the Ohrdruf subcamp, 6 April 1945.

In early April, the SS began to clear the Buchenwald subcamps . They sent the prisoners on transports back to the main camp. In several subcamps, such as Ohrdruf, they murdered those prisoners who were unable to march. US soldiers entered the camp on 6 April 1945.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"The next day, the 10th of April, our complex was also to be evacuated. We hid wherever we could - in the hollow space between the boarding and cladding of the barrack wall, in the dark, musty and narrow space under the floor, under and in the stuffy straw sacks, or we squeezed ourselves into some stinking, vermin-infested sewage pit and refused to leave the block."

Account by Thomas Geve on his hiding place in Buchenwald's Little Camp, 1993.

The children and young people from Block 66 were also to be transported shortly before liberation. Many were able to hide and, like Thomas Geve (born Stefan Cohn in 1929), were liberated at Buchenwald on 11 April. Others were forced by the SS onto death marches, with a few escaping en route or being liberated by the Allies.

(Thomas Geve, Geraubte Kindheit, Constance 1993)

"Comrades, we have the camp in our hands!"

Account by Rolf Kralovitz of the liberation, 1995.

Rolf Kralovitz was 19 years old on the day of liberation and was in the main camp. In this interview he recalls how he perceived the liberation from “inside”.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"When the door opened in the afternoon and two uniforms came in and these uniforms were different from the ones I was used to seeing for six years. But it is not only the uniforms, but the behavior of these two soldiers that made me understand that I was finally free. Tears of joy were then stuck in my throat."

Recollection by Leon Reich of his liberation in Buchenwald, 2015.

Unlike the prisoners in the main camp, the children and young people in Block 66 of the Little Camp saw little of what happened on the day of liberation. Leon Reich recalls this moment in an interview for the MDR film Die Kinder von Buchenwald (The Children of Buchenwald).

(MDR/Buchenwald Memorial)

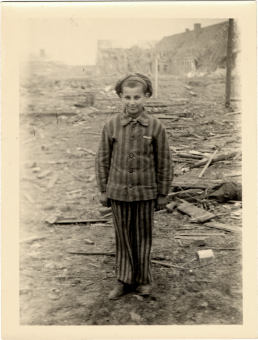

Stefan Jakubowicz (now Stephen B. Jacobs) during a roll call after liberation, 1945.

On the day of liberation, Stefan Jacubowicz was five years old. He had been deported to Buchenwald with his father and brother in December 1944 and had survived thanks to the support of political prisoners in the Little Camp. In June 1945, he was brought to Switzerland with 300 other children as part of the Swiss relief operation. In 2002, he designed the memorial to the victims of the Little Camp at the Buchenwald Memorial.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"There were still some able-bodied prisoners in the camp who had hidden in the infirmary before the camp was evacuated and now began to 'organize' something. They left the camp and brought back bread, milk, butter, bacon, potatoes, and even cigarettes they had found in a factory in Nordhausen."

Account by Roger de Coster, circa 1991.

The 16-year-old Belgian was one of about 80 prisoners liberated by US soldiers in the infirmary of the Dora camp on 11 April 1945.

(Mittelbau-Dora Memorial)

Liberations

Nothing found.

FRIENDSHIP SIBLINGS PARENTS

In order to survive, children and adolescents in the camps needed the help of friends, family members or adult fellow prisoners. Especially for the children, bonds with other people were important in order not to lose the will to live. Relationships helped with the procurement of food and clothing. It could be life-saving to be assigned to a lighter work detail with the help of prisoner functionaries.

Most of the children and adolescents came to Buchenwald or Mittelbau-Dora alone. Only a few were accompanied by their parents or siblings. Some suffered the loss of their relatives in the camps.

"And down here I will write the date when I will see my dear and beloved mother and father again in health". Excerpt from the notes of Alex Hacker, 10 February 1945.

In his secret diary kept during his imprisonment in the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, Alex Hacker prepared an entry for the day of his return home, leaving a blank for the date. He was finally able to fill it in when he returned to his hometown of Budapest on 28 August 1945.

(private property)

Ludwig Hamburger:

The only good thing was, we didn't lose heart.

David Boder:

You didn't lose heart - how did that happen?

Ludwig Hamburger:

I always had my parents in mind [...] How I was a child [...] you have to stay brave and I always heard my mother and thought of my mother.

Ludwig Hamburger in an interview with David P. Boder, 28 August 1946.

Ludwig Hamburger was born in Katowice (Poland) in 1927. He and other young people from Katowice were deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp in 1941. In the winter of 1944, the SS sent him on a death march to Buchenwald. After the camp was liberated, he travelled on an aid transport to a Displaced Persons Camp in Geneva, Switzerland, where David Boder interviewed him in 1946. The last time he saw his mother was in 1941.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

Naftali Fürst (left) and his brother Shmuel in Bratislava, 1936.

The brothers Naftali and Shmuel Fürst arrived at Buchenwald from Auschwitz in January 1945. Prisoner functionaries saw that both boys were housed and protected in Children’s Block 66 in the Little Camp. Naftali was liberated there on April 11, while his brother Schmuel was sent by the SS on a death march and not liberated until early May 1945. The brothers reunited in Bratislava in the summer of 1945.

(private property)

"I always say that in the camps the easiest thing was to die, give up and die. The hard thing was to keep going and fight. And there we had to fight for our lives and every step was a struggle. And I can also say, I am convinced that because we were two brothers together, that helped us a lot. To be alone, a ten- or eleven-year- old child, I don’t think I could do that, because that would be terrible. We were dead tired, dead hungry, wet, you can't imagine."

Naftali Fürst in an interview in Haifa, 2009.

The two brothers Naftali and Shmuel Fürst survived the death march from Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald in the winter of 1945 under the most adverse conditions. The brothers’ bond helped them in their struggle for survival.

(erinnern.at)

Friendship in the concentration camp: Ludwig Hamburger interviewed by David P. Boder, 26 August 1946.

Ludwig Hamburger and his friend survived a death march from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald, where they were liberated. They subsequently went to Switzerland together.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

Liberated Jewish children in Buchenwald, 20 April 1945.

Second from the right in the second row is Markus Milstein. His brother Shraga was taken to Bergen-Belsen in January 1945 and liberated there. The Milstein brothers, like other boys in the photo, were from Piotrków Trybunalski and stayed together as a group in Buchenwald. The group included Israel Meir Lau (front row, second from right). He was the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel from 1993 to 2003.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"I was part of the group. I was never really alone, and it helped because we had a common fate." Account by Shraga Milstein, February 2021.

In the interview, he mentions the photo from Buchenwald showing his liberated brother Markus.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"There was this boy … and I become a little bit friendly with him, you know? This was end of ’42. End of ’44, or January 1945, when I go to this Kinder barrack in Buchenwald, the boy is there. I recognize him, you know? And he recognizes me. This is almost two years later. … The first thing he does, he takes out half of his bread and gives me. And you know, a piece of bread in Buchenwald, I can tell you is like life."

Piece of bread. Jack Aizenberg in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 8 July 1997.

Jack Aizenberg was deported to Buchenwald as a 16-year-old in the winter of 1944. After liberation, he emigrated to Manchester, England, where he was placed in a home with other former Buchenwald prisoners. For some time he also lived there with his friend Pinchas Koronitz, whom he had met in Buchenwald.

(Visual History Archive)

Realms of Experience

Nothing found.

Kurt Ansin

A Sinto from Magdeburg

Month: March 2021

Kurt Ansin was born on 2 October 1921. He grew up in Magdeburg. Beginning in the mid-1930s, the Sinti living there were banned from all public places and placed under constant police surveillance. The Ansin family was forced to move to the Holzweg “Gypsy camp” in 1938.

In the course of the Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich (Operation Work-Shy Reich), Kurt Ansin and his father were arrested in June 1938 and sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, where his father died. Kurt Ansin was released in 1939 and returned to Magdeburg. In 1943, however, he was arrested again and deported with his family to the “Gypsy family camp” at Auschwitz-Birkenau. From there, the SS transferred him via Buchenwald to the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp in 1944.

Kurt Ansin survived, but almost all of his relatives were murdered. He married and had eight children. In 1984, at the age of only 61, he died of the physical and psychological conditions that were direct consequences of his time in the camp.

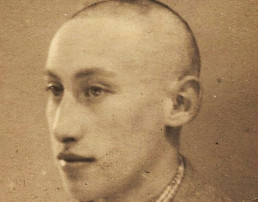

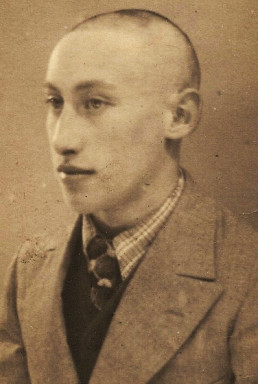

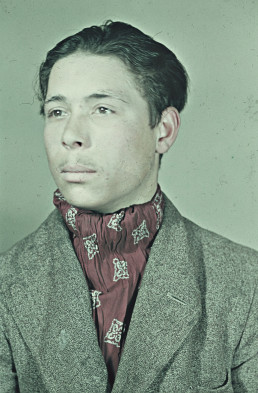

Kurt Ansin, February 1940.

Employees of the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle (Racial Hygiene Research Unit) under the direction of Robert Ritter and Eva Justin took this photo of Kurt Ansin in the Magdeburg forced labor camp. Shortly before, the Magdeburg police had registered all Sinti as alleged criminals and created a “Gypsy file.”

(Buchenwald Memorial)

Kurt Ansin (right) at the age of 15 with a friend, 1937.

Until 1938, Kurt Ansin lived with his family in Dessau-Roßlau. He was one of the few of the Sinti minority there who survived. His friend next to him, who was the same age, was murdered in Auschwitz, as were his siblings.

(Hanns Weltzel/ University of Liverpool Library)

The Gypsy Camp at Großer Silberberg in Magdeburg.

In May 1935, the city of Magdeburg established the Gypsy Camp Magdeburg Holzweg, to which Kurt Ansin, along with the other Sinti from Anhalt, was sent shortly before his arrest in 1938. In the camp, the Sinti lived under miserable conditions and constant police surveillance.

(Stadtarchiv Magdeburg)

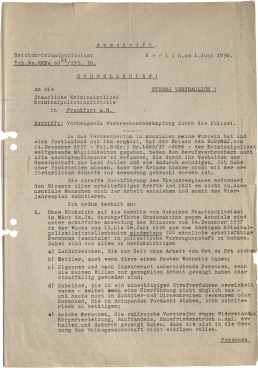

From Auschwitz back to Buchenwald. Kurt Ansin’s prisoner registration file, 17 April 1944.

In April 1944, the SS once again sent Kurt Ansin from Auschwitz to Buchenwald and shortly thereafter to the Ellrich-Juliushütte and Harzungen subcamps. There, he was assigned to the brutal construction forced labor detail.

(Arolsen Archives)

Nothing found.

"My grandfather was the only survivor of eleven siblings. Only his mom and he were left. You have to imagine that: They really wanted to wipe us out. My grandfather was later a broken and ruined man. But we are a very proud people. So, my grandfather's goal was to rebuild a big clan - that we might become many again."

Report by Janko Lauenberger about his grandfather Kurt Ansin, August 2012.

Kurt Ansin, his mother Anna Donna Ansin, and Adelheid Krause were the only three survivors of the Magdeburg Gypsy Camp. Despite this, he was initially not recognized in the GDR as a victim of the Nazi regime. His grandson recalls the family history.

(TAZ)

Hauled off to Concentration Camps

Nothing found.